According to mission controllers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), in Pasadena, California, the NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) was recently able to observe some dark markings on the surface of the Red Planet, which may be indicative of seasonal water flows on our neighboring world.

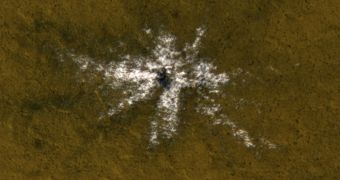

What this implies is that salty water, or brine, may still flow freely on the surface of Mars, surprisingly close to the Martian equator. The attached image shows a crater that formed sometime between 2008 and 2013, and which reveals signs of buried ice right beneath the planet's surface, near the equator.

MRO observed a series of slopes inside Valles Marineris, which is the largest canyon discovered in the solar system. As the seasons passed, slender dark markings waxed and waned, suggesting that they carried liquids to the bottom of the canyon.

The NASA probe is uniquely suited for this type of investigations. It has been surveying the surface of the Red Planet since mid-2006, and has thus far relayed more than 200 terabits of data back to Earth. The new investigation was conducted using its High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera.

“The equatorial surface region of Mars has been regarded as dry, free of liquid or frozen water, but we may need to rethink that,” explains University of Arizona in Tucson researcher Alfred McEwen, who is the main investigator for the HiRISE instrument.

The slender features in Valles Marineris were first reported in 2011. At that time, MRO data revealed that each of these runoffs was just 5 meters (16 feet) wide, and that they could endure at mid-latitudes. These featured endured from spring to early autumn, and disappeared in the winter, only to return the following spring.

New MRO data show that the longest of these dark markings measured 1,200 meters (4,000 feet). Additional details of the research were published in the December 10 online issue of the top scientific journal Nature Geoscience.

“The explanation that fits best is salty water is flowing down the slopes when the temperature rises. We still don't have any definite identification of water at these sites, but there's nothing that rules it out, either,” McEwen concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //