Evidence from a new investigation would appear to suggest that the Martian surface was once so frigid that it contained a primeval ocean, filled with glaciers and icebergs.

The new discoveries do not support any of the two leading theories on how Mars looked like in the past, but rather hint at a third idea, that was previously not proposed.

Thus far, experts believed that the planet may have looked in two different ways in the past – it may have been either cold and dry, or warm and wet. But the findings do not match any of these scenarios.

Rather, they match a third proposition, which states that the planet may have had a wet and cold climate past, in which semi-frozen oceans were covered partially in floating icebergs.

Massive polar ice caps would have existed at both the North and South Poles, researchers say, consistent with the discoveries made by the Phoenix Mars Lander at the high latitudes of Mars.

For th purpose of the new study, the researchers started focusing their attention on a feature that has long since been considered the remnant of a former Martian ocean, the flat, smooth, featureless Martian lowlands, Space reports.

According to investigators, the presence of iceberg traces on the Red Planet could be equated to the presence of large bodies of liquid water on the surface of the planet.

“The size of the water bodies may have ranged from several local seas to a single hemispheric ocean, and they may have been continuous in time or episodic,” explains Alberto Fairen.

He holds an appointment as an astrobiologist at both the SETI Institute and the NASA Ames Research Center (ARC), in Mountain View, California.

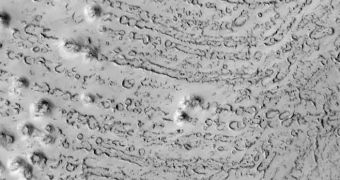

While analyzing the northern plains of Mars with the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), researchers discovered some anomalies in the area.

The images revealed for example the presence of boulders, ranging in diameter from about 1.5 to 6.5 feet (0.5-2 meters). Chains of craters some 330-1,300 feet (100-400 meters) in diameter were also identified in the images.

These discoveries are hard to reconcile with the floor topography that would have resulted from fine-grained sediments depositing themselves at the bottom of a calm ocean.

Details of the new investigation were presented this April, at t the Astrobiology Science Conference.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //