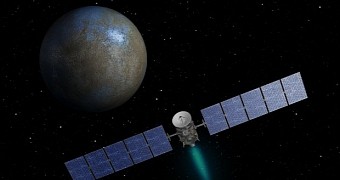

Earlier this week, NASA’s Dawn spacecraft finally completed an epic years-long journey. In a nutshell, the probe reached dwarf planet Ceres and placed itself in its orbit.

The spacecraft is now circling the celestial body and will continue to do so for many months to come. During this time, it will image its surface in unprecedented detail and document its makeup.

If we’re going to be honest here, we have to admit that we have plenty of mysteries to sort out here on Earth. Ours seas and oceans, together with their biodiversity, are still somewhat of a riddle.

There are certain natural phenomena that we do not yet fully comprehend and we don’t know exactly how our Moon formed. Not to mention the fact that elusive Loch Ness monster still hasn’t been found.

Hence, some might be tempted to ask why we’re spending money on exploring worlds gazillions of kilometers (about 1.6 gazillion miles, give or take a few times the distance Frodo had to walk to get to Mordor ) away from us.

Well, the fact of the matter is that there are a few very good reasons scientists saw fit to invest time and money in sending the Dawn spacecraft to Ceres, and they have more to do with our planet than some would suspect.

Crash course in NASA’s Dawn mission

The Dawn spacecraft left our planet on September 27, 2007, when it was launched from the Cape Canaveral Space Station in Florida, US, aboard a Delta II rocket.

On July 16, 2011, the probe reached Vesta, one of the largest asteroids in the Solar System, and got to work orbiting. The spacecraft continued stalking this celestial body until late 2012, when it resumed its journey to Ceres.

A couple of days ago, on March 6, 2015, the spacecraft reached its target. As detailed by mission scientists, it was at 4:39 a.m. PST (7:39 a.m. EST) that the probe was captured by the Ceres’ gravity.

About an hour later, at 5:36 a.m. PST (8:36 a.m. EST), the signal confirming that Dawn had successfully managed to place itself in the dwarf planet’s orbit reached Earth.

In case anyone was wondering, the probe traveled about 3.1 billion miles (4.9 billion kilometers) to reach its target. When it was captured by its gravity, Dawn was just 38,000 miles (61,000 kilometers) away from Ceres.

Why this space mission matters

First off, perhaps we should explain what astronomers mean when they say that Ceres is a dwarf plant. Especially since its size has very little to do with it. In fact, this celestial body is estimated to have a diameter of about 590 miles (950 kilometers).

The thing about Ceres is that, unlike Earth and other celestial bodies considered proper planets, it has not yet managed to clear its orbit. Thus, it is part of our Solar System’s so-called Asteroid Belt and accounts for roughly 30% of its mass.

Unlike other planets, which ancient astronomers were all too familiar with, Ceres was not discovered until January 1801, when space enthusiast Giuseppe Piazzi chanced to see it through his telescope.

The reason astronomers cannot wait to learn more about dwarf planet Ceres is that, although some might not think its size to be all that impressive, the fact of the matter is that this celestial body is the absolute largest thus far discovered in the asteroid belt.

In fact, it is the largest object between the Sun and Pluto that no spacecraft ever visited until this past March 6, and we all know how passionate about making history most scientists are.

Besides, whatever data the Hubble Space Telescope has until now been courteous enough to provide indicates that this celestial body could hide liquid oceans in its entrails, maybe even all the right ingredients for life.

Still, the chief reason this mission was launched was that, by studying Ceres, astronomers hope to learn more about the formation of the Solar System, Earth included.

Like the asteroid Vesta, dwarf planet Ceres is essentially a remnant from when all the planets that comprise our cosmic neighborhood were born. What this means is that, as far as scientists are concerned, they are kind of, sort of like time capsules holding the secrets of how we came to happen.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //