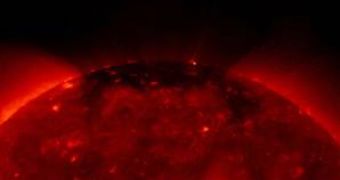

For the first time, physicists have been able to make a link between the magnetic waves on the Sun's surface and its increased atmospheric temperature. The so-called Alfven waves are capable of determining massive differences in temperature between the surface and the corona, some exceeding a ratio of one hundred. As they move across the Sun, the Alfven magnetic waves carry energy from the surface towards its atmosphere.

Ever since their discovery, Alfven waves have been considered a mechanism of radiating heat. However, while the Sun's violent surface only reaches a few tens of hundreds degrees Celsius, its much quieter atmosphere is somehow heated to temperatures of millions of degrees. Now, scientists found proof that indeed Alfven waves could be held responsible for the extreme heating process of the corona.

Researchers from Lockheed Martin Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory used the Japanese solar orbiter Hinode to observe the region of space in the Sun between the surface and its corona, what scientists refer to as the chromosphere. Almost immediately, Hinode was able to observe the Alfven magnetic waves in the chromosphere, and proved that they are intense enough to generate the exceeding temperatures in the corona and to power the solar wind activities at the same time.

Bart de Pontieu, one of the physicists that worked on the study, reveals that, even with Hinode's observations of the Sun's chromosphere, there are not enough evidences to link the magnetic activity to the corona, as they may not be powerful enough to reach the required altitudes to determine such effects. De Pontieu said that long term studies on the Sun have shown that not all the magnetic waves are able to penetrate through the chromosphere and eventually part of them may be reflected backwards towards the surface, not to mention that the detections of magnetic activity in the upper layers of the atmosphere are extremely difficult with the current technology.

On the other hand, computer simulations may provide with some additional information regarding the Sun's magnetic activity. So, with the help of researchers from the University of Oslo, de Pontieu was able to recreate a computer simulation of a part of the Sun's corona. Incredibly, the initial results seem to confirm the theory, as the simulated corona presents strong evidence of magnetic activity that can be directly associated with the Alfven waves in the chromosphere.

Nevertheless, much remains to be learned about the Sun's magnetic activity. For example, a special type of Alfven wave generated by the temperature differences on the surface would eventually snap and reconnect each other, generating powerful X-ray emissions in the process. It is yet unclear if Alfven wave could be held responsible for the high atmospheric temperature, albeit future observations of the corona will demonstrate if the theory is correct or not.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //