Using scientific measurements collected by the Hinode satellite, experts at the University College London (UCL), in the United Kingdom, have recently determined that the main triggers for solar winds in our Sun must be the very strong magnetic fields. While the winds have been known as a phenomenon for a long time, the exact mechanism involved in their formation has yet to be completely deciphered. The new study relies on using the excellent capabilities of the Extreme Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrometer (EIS) instruments, aboard the Hinode satellite.

The observatory, which was built by Japan, the United States and the UK, is currently in the process of collecting large amounts of very precise data, in a highly organized manner. Experts operating it hope that the machine will be able to finally answer the 50-year-old question on how solar winds form. According to the newest study done on the Hinode data, it may be that a process known as slipping reconnection is responsible for generating the solar winds, the UCL team believes.

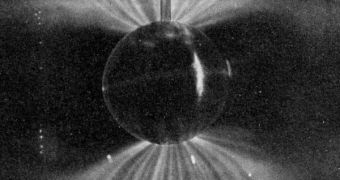

“Solar wind is an outflow of million-degree gas and magnetic field that engulfs the Earth and other planets. It fills the entire solar system and links with the magnetic fields of the Earth and other planets. Changes in the Sun's million-mile-per-hour wind can induce disturbances within near-Earth space and our upper atmosphere and yet we still don't know what drives these outflows,” CL Mullard Space Science Laboratory expert Deb Baker says. The scientist has also been the lead author of the new study, which appears in this month's issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

“However, our latest study suggests that it is the release of energy stored in solar magnetic fields which provides the additional driver for the solar wind. This magnetic energy release is most efficient in the brightest regions of activity on the Sun's surface, called active regions or sunspot groups, which are strong concentrations of magnetic field. We believe that this fundamental process happens everywhere on the Sun on virtually all scales,” Baker adds.

After analyzing previous studies, experts concluded that observing outflows over regions of the Sun that had a single magnetic sign was very improbable. However, using computer simulations, the UCL team has revealed that this, in fact, happens quite often. Measurements indicate that the gas on the surface of the star is moving outward at up to 100,000 miles per hour, which is about 1,000 times faster than the speed hurricane winds have. The data used in this study was collected by the EIS instrument in February 2007, the team concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //