One of the most important goals in physics today is achieving nuclear fusion, the type of reaction that powers up the Sun. Rather than splitting atoms, this nuclear reaction actually merges the nuclei of deuterium and tritium atoms, producing helium and vast amounts of energy, However, designing a working nuclear fusion reactor prototype has proven to be difficult beyond reach up to this point. An experimental device has finally yielded the first clues as to how to make plasma more concentrated, something that is known to boost the rate at which atoms merge, ScienceDaily reports.

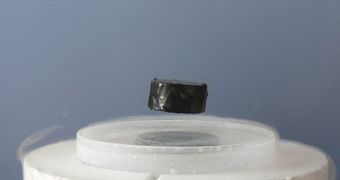

The Levitated Dipole Experiment (LDX) is a joint project, operated by the Columbia University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). It is made up of a very powerful, donut-shaped magnet, which contains superconducting wires, coiled inside a stainless steel vessel. It levitates in a very strong magnetic field, and features a 16-foot-wide outer chamber. This chamber contains electrically charged gas at a temperature of about ten million degrees, which is called plasma. Rendering this plasma more concentrated makes interactions between the atoms within more likely to occur, and therefore boosts the rate of success in achieving nuclear fusion.

The team operating the LDX basically discovered that turbulences occurring in the plasma were what made it more concentrated. This is counter-intuitive, as one would expect such chaotic movements within to decrease the overall efficiency of the system. Physicists reveal that this type of interactions is the same that satellites observe as happening when solar flares hit the upper layers of atmospheres such as the ones around the Earth and Jupiter. Researchers at MIT, where the LDX is stored and operated, say that this is the first time a similar effect has been obtained in controlled, laboratory settings. Details of the work are published in this week's issue of the respected scientific journal Nature Physics.

“It's the first experiment of its kind, [and it] could produce an alternative path to fusion,” the MIT LDX physics research group leader and senior scientist Jay Kesner explains. He is the co-director of the new project, alongside CU Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science Professor of Applied Physics Michael E. Mauel. “Fusion energy could provide a long-term solution to the planet's energy needs without contributing to global warming,” the CU expert says. “LDX is one of the most novel fusion plasma physics experiments underway today,” the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory Director, Stewart Prager, adds.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //