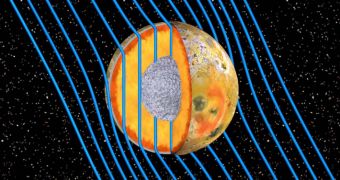

The crust covering the Jovian moon Io may also be keeping a vast ocean of magma buried just beneath the surface from spilling out. According to the conclusions of the latest study conducted on this object, it would appear that the underground layer of molten rock spreads all over the moon.

This may provide an explanation for why Io is the most volcanically-active object in the solar system. Even its appearance is indicative that something nefarious is going on beneath its surface, experts say.

The research also revealed some differences between the situation on Io and that on Earth. On our planet, magma can only be found close to the surface in regions where tectonic plates meet.

Only here can the molten rock climb towards the surface, and find a way out through the crust via volcanoes. But things are quite different on the Jovian moon, where the magma extends uniformly throughout the planet, just a small distance beneath the surface.

This global reservoir, as experts call it, is about 30 miles (48 kilometers deep), investigators say. This could help explain why the volcanoes on Io spew out about 100 times more lava than all the volcanoes on Earth combined.

“Now we know where all of that lava is coming from,” explains Krishan Khurana, the lead author of a new paper detailing the findings, and a geophysicist at the University of California in Los Angeles.

Io is very similar to our Moon, in the sense that the two objects have about the same size, and they orbit their respective planets at about the same distance. But Io is only the third-largest moon of Jupiter.

But this close proximity is tearing the object apart, literally. Given its huge size, the gas giant is exerting tremendous gravitational and tidal forces on Io, and these go a long way towards keeping its inner regions active.

As tidal forces pull on the moon's core, the various layers within start to grind against each others, and this friction causes the heat the drives the magma ocean under the surface. “It's always wonderful to have some direct proof,” Khurana says of the new explanation.

Datasets used in the new investigation were collected by the NASA Galileo spacecraft between 1995 and 2003, as it conducted its investigations of Jupiter, its ring system and its moons, Space reports.

Studying Io could help experts gain a deeper insight into how plate tectonics and volcanism began here on Earth, during the early days of the solar system. Taking into account the importance of these phenomena in supporting the development of life, experts are quite anxious to get there.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //