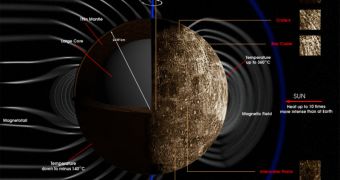

Recently, NASA's MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft performed its third and final flyby of the innermost planet in our solar system. The flight was meant to cover the knowledge gaps left behind by the other two flybys, and to finish mapping the remainder of the planet's surface. While it indeed managed to do all that, the space probe was also able to take images of a very peculiar crater on the surface of the planet, which looks like it experienced some volcanic activity not more than one billion years ago, which is fairly recent by geological standards, Nature News reports.

According to Southwest Research Institute (SRI) planetary scientist Clark Chapman, the rocks at the tip of this particular crater are the newest on Mercury, and the last to have formed following volcanic activity in the planet's core. The Boulder, Colorado-based researcher is also a member of the MESSENGER mission team. He reveals that the crater, which has yet to be named, has a diameter of more than 260 kilometers (some 161 miles), and resembles another one, discovered in early 2008. That formation was named Raditladi, and the similarity between the two has made some team members refer to the new crater as the Twin.

The main difference between the two is the fact that the Twin is riddled with a lot less small craters than Raditladi, which means that it was exposed to meteorite bombardment for a lot less time than its “cousin.” “That's just absolute proof of volcanism. It's hard to say, but it could be less than a billion years old,” Chapman revealed at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America, in Portland, Oregon. The meeting took place on October 20. The new find is very important because geologists and planetary scientists believed that Mercury's period of volcanic activity ended some three billion years ago. Two billion years is a big difference, they note.

“We're getting an intriguing look that even as close to the Sun as Mercury there may be some process for delivering and retaining volatiles to the interior that we did not appreciate,” Carnegie Institution in Washington expert Sean Solomon said. He added that the planet might have also had a significant tectonic-activity history, as evidenced by the four overlapping cracks in the 715-kilometer-wide Rembrandt Basin. “[They] point to Mercury being an even more tectonically interesting place than we suspected either from Mariner 10 [in 1974] or the first two [MESSENGER] fly-bys,” Solomon added.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //