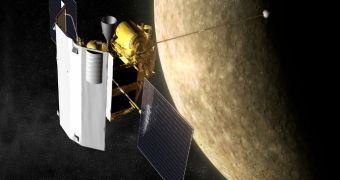

Six days from now, a NASA spacecraft is scheduled to become only the second American space probe ever to enter orbit around Mercury, the closest planet to the Sun. The event will mark the beginning of a new series of studies, that will answer some very interesting questions about this celestial body.

The vehicle launched on August 3, 2004 at 06:15 UTC, from the Space Launch Complex 17B (SLC-17B) at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS), in Florida. It soared to the skies aboard the Delta II 7925 delivery system.

It has been flying through the inner solar system for 6 and a half years. During this time, it carried out a flyby around Earth, two close passes by Venus, and three around Mercury. All of them were carried out for a double purpose.

They were meant to help experts calibrate the instruments aboard the spacecraft, to get new insight about Venus, and also to calibrate the probe's orbit, in order for a March 17, 2011 insertion date to become possible.

“We can look forward to an enormous increase in understanding of one of our nearest planetary neighbors. [Achieving orbital insertion is] the culmination of the mission, the principle objective,” explained Sean Solomon.

The expert, who is based at the Carnegie Institution of Washington (CIW) Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, is the principal investigator of the NASA MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) mission.

He made the statement in February 2011, while speaking at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS 2011), Space reports.

All the spacecraft has to do in order to achieve orbital insertion is to begin a 14-minute engine burn at 8:45 pm EDT on March 17. NASA experts estimate that, by April 4, the probe will be able to begin conducting scientific studies of the planet.

“We cannot wait for orbital insertion. The science team is ready to start taking orbital observations, so we are very much looking forward to what all of us hope is a successful orbit insertion into the desired science orbit,” Solomon explains.

This is also the most dangerous stage of the mission, the expert adds, as evidenced by the failure of the Japanese Akatsuki weather satellite, which was heading for Venus. A failure in its engines during the scheduled thruster burns did not allow for it to be captured in Venusian orbit.

As a result, experts with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) will get another shot at performing the maneuver in late 2016 / early 2017. Hopefully, MESSENGER will fare better than Akatsuki.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //