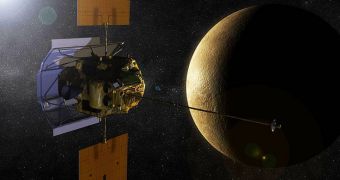

Datasets relayed back to Earth by the NASA MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft are painting an increasingly clearer image of the closest planet to the Sun. Astronomers now know more about the planet than ever before.

MESSENGER is the first-ever spacecraft to be injected in Mercurial orbit. Other probes have flown by the planet, analyzing it in passing, but none took a stable orbit around the hot space rock, to analyze it in detail and for prolonged periods of time.

Now that the NASA probe is doing that, scientists are beginning to learn a lot of new things, such as for example how the planet originated, the significance of its geological history, the way its interior is set up, and how atmospheric processes take place at the surface.

The probe achieved orbital insertion around the innermost planet on March 18, and mission controllers have since commissioned all of its instruments to conducting scientific investigations. This led to the creation of high-resolution maps of the surface.

MESSENGER also collected global data on the planet's magnetic field, its intensity and its effects. Surface topography is also cataloged and imaged, as is the chemical composition of the air and soil.

As the planet's magnetic fields interact with the solar wind, bursts of energetic particles occur in Mercury's atmosphere constantly. Thus far, experts were unable to pinpoint the exact source of these phenomena, but the mystery is cleared now.

“We are assembling a global overview of the nature and workings of Mercury for the first time. Many of our earlier ideas are being cast aside as new observations lead to new insights,” says Sean Solomon.

“Our primary mission has another three Mercury years to run, and we can expect more surprises as our solar system's innermost planet reveals its long-held secrets,” adds the Carnegie Institution of Washington expert, who is the principal investigator of the mission.

The spacecraft was also able to image bright, patchy deposits on some crater floors in more detail. Previously, flybys had only imaged these locations in low-resolution, but the new data indicate the existence of clusters of rimless, irregular pits inside the craters.

“The etched appearance of these landforms is unlike anything we've seen before on Mercury or the Moon,” explains MESSENGER imaging team member Brett Denevi, who is also a staff scientist at the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), in Laurel, Maryland.

“We are still debating their origin, but they appear to be relatively young and may suggest a more abundant than expected volatile component in Mercury's crust,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //