On April 4, the first spacecraft ever to orbit the innermost planet in the solar system will begin its science mission. Experts hope that the suite of instruments aboard the probe will help them get more insight into some of the things that have puzzled astronomers for years.

Chiefly among those is whether the planet hosts water-ice. Though it may seem counter-intuitive at first, given its close proximity to the Sun, some believe that the material may still endure in some of Mercury's deepest, permanently-obscured craters.

Mission scientists at the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, say that finding water-ice is one of the primary objectives for the spacecraft.

Average temperatures on the planet can reach 842 degrees Fahrenheit (450 degrees Celsius) on the surface, but experts say that past missions have revealed the existence of deep, dark craters in the polar regions. These structures may still contain water-ice.

The MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft arrived in orbit around the planet on March 17, after 6 and a half years of flying through the inner solar systems, experts say .

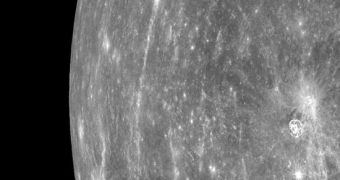

Starting in early April, it will begin a 1-year mission to analyze Mercury in detail. Efforts will also include snapping an estimated 75,000 images, that will then be stitched together to form a new map depicting the Mercurial surface.

“We're really seeing Mercury now with new eyes. As a result, an entire global perspective is unfolding, and will continue to unfold over the next few months,” said yesterday, March 30, Carnegie Institution of Washington MESSENGER principal investigator Sean Solomon.

“Could ice be trapped there? The thermal models say yes, it's possible. But is it water ice? There are alternative ideas,” he adds. Radar data first identified reflective materials at the Mercurial poles some two decades ago, and this is what informed experts that the stuff may still exist there.

In addition to solving this riddle, the space probe will also seek to determine why Mercury is so dense in comparison to Mars, Earth and Venus. MESSENGER will also analyze the magnetic field surrounding the planet.

Another segment of the mission calls for the spacecraft to investigate aspects of Mercury's history and internal composition. This includes learning more about the way its interior is layered and structured.

“All subsystems and instruments are on and operating nominally, within specifications. This is a tremendous achievement for the entire Messenger team,” says JHU-APL expert Eric Finnegan, who is a mission systems engineer for MESSENger.

“We are rapidly ramping up a much larger dataset with which to characterize the geometry of Mercury's magnetic field. That will tell us a lot about Mercury's internal structure and dynamics,” Solomon concluded, quoted by Space.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //