Scientists from the Wake Forest University School of Medicine have recently announced the successful use of a new, small peptide to efficiently stop the growth of lung cancer tumor cells. Their paper also reveals that the small molecule also had the strength of setting the tumor into remission, reducing its size considerably. The research appears in the latest issue of the American Association for Cancer Research's journal Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, ScienceDaily reports.

“If you're diagnosed with lung cancer today, you've got a 15 percent chance of surviving five years – and that's just devastating. Those other 85 people – 85 percent – they're not going to see their kids graduate. They're not going to see their children get married,” Patricia E. Gallagher, PhD, who is the co-lead investigator of the new study, says of the terrible disease. She is also the director of the WFUSM Hypertension and Vascular Research Center Molecular Biology Core Laboratory. The new peptide, dubbed angiotensin-(1-7), works by inhibiting blood-vessel formation.

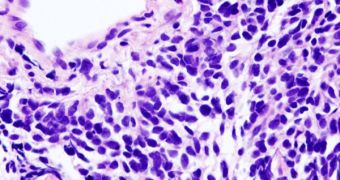

Peptides are fundamental building blocks of life, composed of certain sequences of amino-acids that bind with each other by exchanging electrons. They can play a number of functions, ranging from regulating hormones to being antibiotics, depending entirely on the sequence of amino-acids that makes them up. In the case of angiotensin-(1-7), the chain is designed in such a way that, when it binds to proteins on the surface of growing cells, it immediately stops the cellular growth. The only condition for it to work is for the cell to be growing when the binding occurs.

“Because it's a peptide, it's very small and can be made very easily. We sometimes like to say we're the aspirin of cancer therapy,” Gallagher adds. The new peptide was found in the team's experiments to have negative effects on angiogenesis, the process through which new blood vessels are formed inside the human body. In mouse embryos treated with angiotensin-(1-7), blood-vessel formation declined by more than 50 percent, as opposed to embryos in a control group, where it continued to rise.

The team believes that the new approach may be used on other types of cancer as well in the future, in spite of the fact that several types of blood vessel-inhibiting methods have already been tried out, sometimes to devastating consequences, such as an accelerated growth. The new research was funded by the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Research Foundation, the US Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Unifi, Farley-Hudson Foundation, and Golfers Against Cancer of the Triad.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //