Investigators at the Brown University announce that they've recently finished compiling a detailed map of how the lithosphere is set up underneath southern California. The lithosphere is made up of Earth's solid crust and parts of its upper mantle, and includes all tectonic plates.

What geologists at the university did was basically use a wide variety of study methods to make sense of the way these plates were organized at this particular location. This is critical because important, geologically-active regions such as the San Andreas Fault Line are located nearby.

With the new research tool at their disposal, scientists can now begin more in-depth studies on the nature of the geological forces that played the most important roles in shaping the landscape to its current form. Details of the study are published in the October 7 issue of the top journal Science.

According to the high-resolution map of the southern California underground, this area is one of the most fascinating and active in the world. It lies at the collision point between the massive North American Plate and the equally-large Pacific Plate.

The Juan de Fuca and Cocos plates are also decisive actors in this regions, though they are a lot smaller than the other two. ”What we’re getting at is how (continental) plates break apart,” research scientist Vedran Lekic explains.

“What happens below the surface is just not known,” adds the expert, who was the first author of the Science paper. The investigator holds an appointment as postdoctoral student at the Brown University.

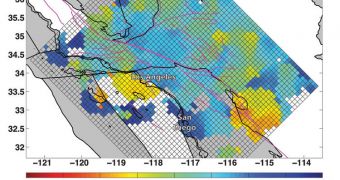

Scientists covered an area including Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, San Diego and the Salton Trough, which measured about 400 by 300 miles (roughly 482 by 643 kilometers). The target of the research was the layer separating the lithosphere from the asthenosphere below, Earth's upper mantle.

Even in such a small area, the thickness of the lithosphere was found to vary widely, ranging from 25 to 60 miles (40 to 96 kilometers). Experts expected to obtain more consistent results throughout the study area.

“We see these really dramatic changes in lithosphere thickness, and these occur over very small horizontal distances. That means that the deep part of the lithosphere, the mantle part, has to be strong enough to maintain relatively steep sides,” Karen Fischer explains.

“This approach provides a new way to put observational constraints on how strong the rocks are at these depths,” adds the Brown professor of geological sciences. Fischer was also one of the authors of the new paper accompanying the research.

The Earthscope program and an Earth Sciences postdoctoral fellowship, both at the US National Science Foundation (NSF), provided the funds needed for this investigation.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //