For a very long time, researchers have tried, unsuccessfully, to turn hydrogen into metal. This is known to be possible, and, probably, this form of the chemical is present on other planets, most likely gas giants, but it's impossible to obtain the material here on Earth. It has tremendously large pressure requirements, which cannot be achieved in today's laboratories. A recent study predicts that turning hydrogen metallic could be achieved while using much lower pressures than first estimated, if something else is added to the mix, the US National Science Foundation (NSF) reports.

Metallic hydrogen is predicted to be a high-temperature superconductor. These materials pose no resistance to moving electrons, which means that electrical currents can flow inside them indefinitely and without losing their properties. In the new, theoretical paper, published in this week's online issue of the respected scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), a team of scientists, based at the Cornell University, and the State University of New York in Stony Brook, reports that adding a bit of lithium to hydrogen might considerably lower the pressure requirements.

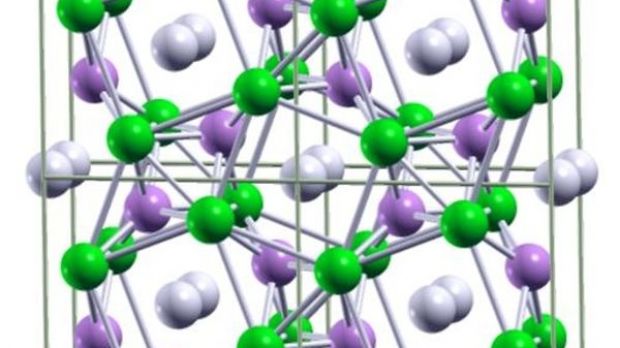

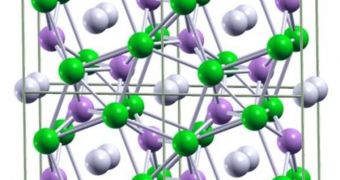

“The stable and metallic LiH6 compound is predicted to form around 1 million atmospheres, which is around 25 percent of the pressure required to metalize hydrogen by itself,” the lead author of the paper, State University of New York in Buffalo Assistant Professor of Chemistry Eva Zurek, explains. “Interestingly, between approximately 1 and 1.6 million atmospheres, all the LiH combinations studied were stable or metastable and all were metallic,” study co-author Roald Hoffman adds. He is the H.T. Rhodes Professor of Humane Letters, Emeritus, at the Cornell University, and also a 1981 Nobel Prize in Chemistry recipient.

“The theoretical study opens the exciting possibility that non-traditional combinations of light elements under high pressure can produce metallic hydrogen under experimentally accessible pressures and lead to the discovery of new materials and new states of matter,” NSF Division of Materials Research Program Director Daryl Hess says. “Once again, these researchers have taken chemistry to a new frontier. They have described, through their theories and calculations, molecules that test our fundamental assumptions about atoms, molecules and structures. In doing so, they challenge the experimentalists to make what they have imagined in their minds a reality to be held in the hand,” NSF Division of Chemistry Program Director Carol Bessel concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //