Stanford University investigators have created a new type of retinal implant, which can partially restore vision in people who suffer from the effects of accidents or medical conditions. The implants contain photovoltaic cells, which means that they can be powered by light.

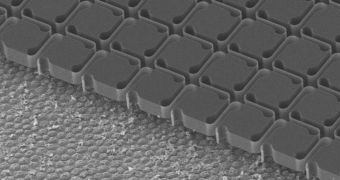

The designers of the medical device say that it represents a crossover between a photovoltaic array and a digital imaging chip. When compared to other retinal prosthetic devices, the new instrument has higher pixel density, and is capable of restoring more vision than any comparable implant.

Up to this point, the devices have not been tested on animals or human subjects, but lab results are showing great promise, and many researchers in the international scientific community are very excited about the new device.

One of the reasons the devices are so appreciated by researchers is that they may help people who lose their sight on account of macular degeneration, the leading cause of blindness in the elderly.

In several forms of blindness, including macular degeneration, light-sensing cells in the retina are lost, but the nerves connecting the back of the eye to that area of the brain in charge of processing visual signals (the visual cortex in the occipital lobe) are still in place.

In these cases, restoring sight is a matter of connecting a sensor capable of picking up light to the nerves that link the eyes to the brain. In other words, surgeons need to replace the natural light detectors in the human eyes with synthetic ones, Technology Review reports.

Retinal implants, such as the one under development at Stanford, contain electrodes that can be placed atop the nerve fibers. When the devices detect light, they release a small electrical current that stimulates the nerves, creating the impression of sight.

Details of how the new Stanford implants work were presented in the May 13 issue of the esteemed scientific journal Nature Photonics. The main innovation the team brought is the fact that researchers used light as both image and power source.

The investigators are currently experimenting with various types, sizes and shapes for their implants. Unfortunately, the technology is still several years away from clinical trials on humans, and even more until it reaches the market.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //