In a paper published in the May 27 issue of the top journal Nature Geoscience, researchers at the University of Bristol, in the United Kingdom, argue that life required around 10 million years to recover following the largest mass extinction in history, the Permian-Triassic (P-Tr) event.

Known as The Great Dying among experts, the extinction left behind only 10 percent of the animal and plant species that existed on Earth before it occurred. It is the only known instance when extinction affected insects.

Scientists widely regard it as the most likely event to wipe out life on Earth completely. Fortunately, that did not happen. Evidence suggests that the extinction may have occurred in one, two or three steps, separated by a few million years. The debate as to what actually happened is still ongoing.

Until the causes are established, researchers continue their work of understanding how life bounced back from the P-Tr. event. UB professor Michael Benton has recently conducted a survey on how long it took species to recover from the extinction, and his analysis places the figure at 10 million years.

Working together with Dr. Zhong-Qiang Chen, from the China University of Geosciences, in Wuhan, the expert determined that this significant delay in recovery (as compared to what happened after other extinction events) was caused primarily by the sheer scale of the devastation.

“It is hard to imagine how so much of life could have been killed, but there is no doubt from some of the fantastic rock sections in China and elsewhere round the world that this was the biggest crisis ever faced by life,” Dr. Chen explains.

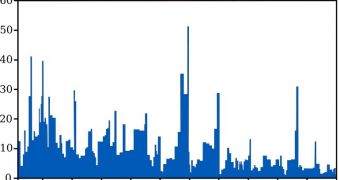

After the first wave of destruction, conditions continued to remain grim for the development of life for as much as 6 million years, the team found. Periods of intense global warming and cooling alternated with spikes and drops in the amount of oxygen and carbon available in the atmosphere.

Another reason why reestablishing ecosystems was delayed is that not enough species were available to create the necessary self-sustaining connections. Only a few groups of plants and animals were able to recover soon after the extinction, but their numbers were too small to make any real impact.

“Life seemed to be getting back to normal when another crisis hit and set it back again. The carbon crises were repeated many times, and then finally conditions became normal again after five million years or so,” explains Benton, who is a professor of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Bristol.

“We often see mass extinctions as entirely negative but in this most devastating case, life did recover, after many millions of years, and new groups emerged. The event had re-set evolution,” he adds.

“However, the causes of the killing – global warming, acid rain, ocean acidification – sound eerily familiar to us today. Perhaps we can learn something from these ancient events,” the expert concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //