In a recent series of experiments, experts were able to demonstrate that the 20 amino-acids currently making up the basis of all lifeforms were not selected at random. Of the 100+ such molecules, this set proved to be the most efficient. This hints at the fact that life can arise on a whim on other worlds too.

For years, experts have been trying to determine the basis required to create life. More often than not, their work focused on the conditions necessary for the development of life, such as a planet's proximity to its parent star, whether or not it held liquid water on its surface, and so on.

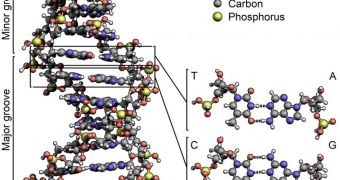

At the same time, chemists and biologists have been working towards studying the molecular bases of life. They recently turned to analyzing amino-acids because these molecules are the foundation of proteins. This makes them some of the most basic constructs lifeforms depend on.

Of the large number of available amino-acids, only 20 are used by living things. What this implies is that this particular combination is the most well-suited for the task at hand. The question that immediately arises is whether another combination could be suitable for life on another planet.

Interestingly, such discoveries lead researchers to believe that some form of natural selection took place among these amino-acids, back when the planet was still very young. Lifeforms have been based on its current amino-acid alphabet for more than 3 billion years.

“It's becoming increasingly clear that many other amino acids were plausible candidates, and although there's been speculation and even assumptions about what life was doing, there's been very little in the way of testable hypotheses,” expert Stephen J. Freeland says.

The expert, who is based at the University of Hawaii's NASA Astrobiology Institute, conducted a study showing life's preferences for the 20 amino-acids alongside colleague Paul Davies, a co-director of the Cosmology Initiative at the Arizona State University (ASU).

He also holds an appointment as the director of BEYOND: Center for Fundamental Concepts in Science. “To the best of our knowledge, the original chemicals chosen by known life do not constitute a unique set; other choices could have been made, and maybe were made if life started elsewhere many times,” Davies explains.

As such, it is entirely possible that life may spontaneously rise on other worlds as well, perhaps based on a set of amino-acids that is identical, or slightly-different, than our own. There would be numerous reasons for some changes to take place, including for example an exoplanets specific environment.

“Technically there is an infinite variety of amino acids. Within that infinity there are lots more than the 20 that were available [when life originated on Earth] as far as we can tell,” Freeland said in an interview for Astrobiology Magazine, Daily Galaxy reports.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //