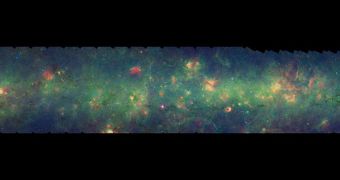

Just yesterday, December 2, the Adler Planetarium in Chicago saw a ceremony during which the world's largest image of the Milky Way was revealed to the public. The photo was made by combining an impressive number of individual images collected by NASA telescopes and stitched together to form the amazing panorama. Experts who were in charge of manipulating the images say that this is one of the most sensitive depictions of our galaxy ever to be taken in infrared wavelengths.

Space reports that the new photograph covered a huge area that was about 37 meters (120 feet) long. The piece of material on which the data are printed is only one meter (three feet) tall at the edges, in the sections where our galactic disk is represented, but gets to be about two meters (six feet) towards the center, where the bulge at the Milky Way's core is depicted. Like most spiral galaxies, when viewed head-on, ours tends to show an increased volume around its central parts, where matter tends to gather around the supermassive black hole that resides there.

The panoramic view was only made possible by two Spitzer survey teams, which used their alloted study time to conduct investigations into the structure of the galaxy. The two groups used one Spitzer instrument each. The former used the Infrared Array Camera (IRAC), while the latter used the Multiband Imaging Photometer. According to logs, more than 800,000 individual images were stitched up to create the new Milky Way image. California Institute of Technology (Caltech) Spitzer Science Center expert Robert Hurt says that the collage covers an area about the width of a fingernail in the night sky, and a length of about one to 1.5 meters. It contains more than 2.5 billion infrared pixels.

“This is the highest-resolution, largest, most sensitive infrared picture ever taken of our Milky Way,” one of the team leaders, Caltech Spitzer Science Center expert Sean Carey, says. “I suspect that Spitzer's view of the galaxy is the best that we'll have for the foreseeable future. There is currently no mission planned that has both a wide field of view and the sensitivity needed to probe the Milky Way at these infrared wavelengths,” scientist Barbara Whitney, who is a Spitzer team member from the Madison, Wisconsin-based Space Science Institute (SSI), adds.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //