In a report published in the open-access journal eLife just yesterday, January 13, researchers with Duke University in North Carolina, US, detail the use of human cells to grow skeletal muscles able to contract in response to electrical stimuli.

The scientists go on to explain that these skeletal muscles that they managed to create in laboratory conditions were so much like native tissue that they even reacted to biochemical signals and pharmaceuticals. The achievement is hailed as a world first.

How the researchers grew the muscle fibers

As explained in the paper documenting this scientific breakthrough, the Duke University researchers were the proud guardians of just a small batch of human cells when they first got to work. From these cells, they managed to grow muscle fibers.

The scientists say that the human cells they toyed with were so-called myogenic precursors. What this means is that, although they were no longer in their infancy in the sense that they were not undifferentiated stem cells, they had not yet become adult muscle cells either.

Simply put, the cells were somewhere in between these two stages of their evolution. To paint a better picture of the evolutionary phase they were in, let's just say that they were the right age for Britney Spears' “Not a Girl, Not Yet a Woman” to deeply resonate with them.

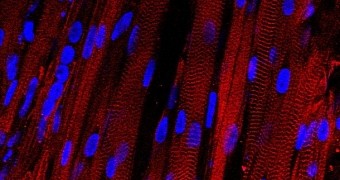

To make their muscle fibers, the scientists first expanded these myogenic precursors 1,000-fold, and then placed them on a three-dimensional scaffolding. While attached to this scaffolding, the cells were drenched in a nourishing gel that encouraged them to keep growing and form muscle fibers.

Once grown, the muscles behaved like native tissue

The Duke University scientists who worked on this research project explain that, having grown the muscles fibers from human cells, they subjected them to a series of tests. In a nutshell, they exposed the muscles to electrical and chemical stimuli.

The researchers found that, when receiving electrical impulses, the fibers reacted just like native tissue, meaning that they contracted. Besides, it is said that, when exposed to drugs such as statins and clenbuterol, the fibers responded to them similarly to muscle tissues that naturally form in the body.

“The statins had a dose-dependent response, causing abnormal fat accumulation at high concentrations. Clenbuterol showed a narrow beneficial window for increased contraction. Both of these effects have been documented in humans,” the scientists detail.

Why this research project matters

Study leader Nenad Bursac and fellow researchers expect that their laboratory-grown skeletal muscle fibers will make it easier for other scientists to better understand all sorts of diseases that affect this type of tissue, maybe even develop and test drugs designed to treat these conditions.

The idea is to experiment on muscle fibers engineered to behave just like native tissue rather than risk administering patients new drugs and hope for the best. In fact, the lab-grown muscles could even serve to develop personalized treatment options for people struggling with muscle diseases.

“One of our goals is to use this method to provide personalized medicine to patients. We can take a biopsy from each patient, grow many new muscles to use as test samples and experiment to see which drugs would work best for each person,” explains specialist Nenad Bursac.

If you have about a minute to spare and happen to be in the mood to get a better idea of what the Duke University scientists did that made them news-worthy, check out the video below.

The footage shows the lab-grown muscles contracting on their scaffolding, and it's pretty entertaining. More so if you're into medicine and the latest advances in cell engineering.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //