A future telescope of the European Space Agency (ESA) could help explain some of the most tightly-kept mysteries in the Universe, such as for example whether gravitational waves exist or not. But the instrument may also test for the existence of vanishing dimensions other than the known three.

Many theoretical physicists argue that the early Universe contained a lot more dimensions shortly after the Big Bang. These dimensions were demonstrably unstable, and they may have collapsed onto each other soon afterwards, producing more stable ones.

The three we have today – length, width and depth – are apparently the most stable, but they may collapse down as well into a single one at very high energy. This line of thought may actually help experts explain numerous things about particle physics.

Right now, the Standard Model of elementary particles is very efficient at explaining most things we want to know about the Cosmos, but it breaks down when it comes to figuring out why the Universe is expanding at an ever-accelerating rate.

The Model also performs poorly when it comes to explaining the high energies and states of matter – such as quark-gluon plasma – that existed in the first moments after the Big Bang. Physicists say that it's incapable of explaining the interactions between the two primary types of physics.

Combining Newtonian physics (which addresses interactions between large-scale objects) with quantum mechanics in a Unified Theory of Everything has been a goal in physics for decades, but all theories developed to this end have thus far failed, Wired reports.

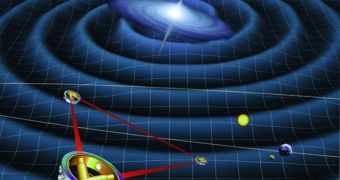

However, in a new study published in the journal Physical Review Letters on March 11, experts provide new hope that these mysteries will be cleared. They say that the existence of extra dimensions will be tested with the launch of ESA Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) system.

“I think people are too attracted to these mainstream models. We may not be seeing the forest behind the trees because of that. We really need a new breakthrough, new experimental data to more forward in this field,” says Brown University physicist Greg Landsberg.

In the journal paper, experts propose that LISA could help test whether the Universe had fewer dimensions in the past than it does today, which is an entirely new paradigm in cosmology.

But if the Universe in fact has only 2 dimensions, then it's mathematically impossible for gravitational waves – LISA's main target – to exist. “There’s no way to get around the fact that gravity waves don’t exist if you have less than three dimensions of space. They just don’t,” says Jonas Mureika.

He holds an appointment as a theoretical physicist at the Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, and is also the lead author of the new study.

“What I find particularly spectacular is that they were able to draw very concrete experimental conclusions. This paper shows the community has finally started appreciating this new way of thinking,” concludes Landsberg, who was not a part of the research.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //