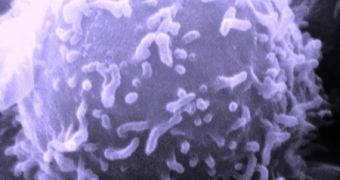

Scientists may have found a way to suppress the ability that cancerous cells have, which is to make the immune system think that they are a natural part of the body. Through this method, they avoid being attacked by the killer T lymphocytes that make up the backbone of our immune system. The immune cells are led to believe that the infections and tumors are a regular occurrence, which is not caused by outside pathogens, so they don't interfere.

The goal of almost all cancer researchers so far was to make them interfere, so that the immune system would realize that something had gone awfully wrong and go about its business to fix the damage. Both innate (passed on) and adaptive immunities are blocked by cancerous cells, mainly because cancer first starts as a mutation inside a body cell. The fact that the mutation was caused by outside factors is unknown to the immune system, since no culprits were detected in the bloodstreams or cells. As far as the lymphocytes are concerned, everything is running smoothly.

But researchers at Scripps Research Department of Immunology came up with various ways of "waking up" the immune system and directing it to the developing tumors. "We have been working for years to find ways to coax these so-called low affinity T cells to work better," explains Linda Sherman, Ph.D., senior investigator in the current study. The scientists managed to create a complex that combines interleukin-2 (IL2) with IL2 antibodies.

When this mix is injected into the bloodstream, killer T cells bind to it and start growing very, very fast, as the complex acts in the same way a growth agent would. Once they are matured, the lymphocytes start releasing cytotoxins in the tumors. These toxins basically contain the "shut down" command for all cells. This means that all activity within cancerous cells ceases completely. To all extents and purposes, the cell is dead.

The drawback of this new technique is that once the IL2 complex is gone, the T lymphocytes degenerate and die very rapidly, which allows for the tumors to grow back. For now, the Scripps team is focusing on finding a human antibody for IL2, so clinical test trials could begin. Hopefully, these lab experiments, conducted on mice, will soon provide oncologists with a new means of stopping cancer dead in its tracks.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //