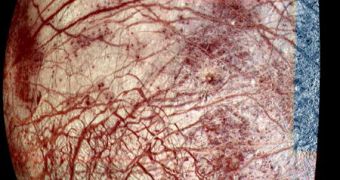

For many years, researchers have suspected that the Jovian moon Europa contains a hidden underground ocean, but now chemists believe that something else may be taking place on the planet as well.

They explain that the deep regions of the moon, and perhaps even its surface, may be home to some fast chemical processes, taking place between water and sulfur dioxide at very low temperatures.

On average, the surface of Europa experiences temperatures of around minus 160 degrees Celsius, or roughly minus 260°F at the Equator, and minus 220°C at the poles.

What puzzled investigators who conducted this new work was the fact that the two chemical elements seem to interact just as well when they are ices, as when they are liquids.

In the latter scenario, water and sulfur dioxide produce acid rain back on Earth. This means that the chemicals readily interact as liquids.

But temperatures on Europa are far too low to allow for the existence of these chemicals as liquids. Ice on the surface of the moon may be even harder and more resistant than granite.

Now, a team of experts from the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC), in Greenbelt, Maryland, believes it may have discovered a mechanism allowing the ices to react with surprising speed.

The work was conducted by GSFC scientists Mark Loeffler and Reggie Hudson, who believe that the reactions take place even at several hundred degrees below freezing point.

This chemical reaction takes place without the aid of radiation, the investigators say, which means that it can happen anywhere on the surface of Europa, from the Equator to the poles.

If the discovery turns out to be true, than this could change the way scientists understand the geology and chemical structures of the Jovian moon, and perhaps other similar celestial bodies.

“When people talk about chemistry on Europa, they typically talk about reactions that are driven by radiation,” explains Loeffler, who is the first author of a new paper detailing the findings.

The work is published in the latest issue of the esteemed scientific journal Geophysical Research Letters, experts at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) report.

“Once you get below Europa's surface, it's cold and solid, and you normally don't expect things to happen very fast under those conditions,” adds Hudson, a coauthor of the paper, and an associate lab chief at the GSFC Astrochemistry Laboratory.

“But with the chemistry we describe, you could have ice 10 or 100 meters [roughly 33 or 330 feet] thick, and if it has sulfur dioxide mixed in, you're going to have a reaction,” adds Loeffler.

“This is an extremely important result for understanding the chemistry and geology of Europa's icy crust,” concludes radiation-induced chemistry expert Robert E. Johnson, who is a professor of engineering physics at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //