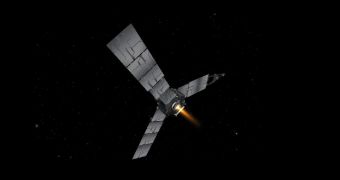

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) scientists watched the telemetry flowing onto their computer screens with great care yesterday, August 30, as data from the Juno spacecraft kept pouring in. The probe, currently on its way to Jupiter, carried out a critical course-correction maneuver yesterday.

Launched on August 5, 2011, aboard an Atlas V rocket, the Juno mission is scheduled to achieve orbital insertion around the gas giant Jupiter, beyond the Inner Asteroid Belt, in early July, 2016. But the probe is not taking a conventional course to the distant world.

It is currently scheduled to perform a flyby of Earth on October 9, 2013. The gravity-assist procedure will slingshot the spacecraft around our planet, increasing its speed significantly, and allowing it to reach Jupiter three years later.

By comparison, the Cassini-Huygens mission launched towards Saturn in 1997, and reached the gas giant in 2004, more than 7 years later. June will be traveling a lot faster, but will feature solar panels instead of radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTG).

It was only through significant scientific advancements made over the past few years that solar panel technology evolved to the point where it can be used efficiently at a distance of 5 astronomical units from the Sun. An AU is the mean distance between the Earth and the Sun, roughly 93 million miles.

JPL investigators say that, if next year's gravity-assist maneuver goes according to plan, Juno will reach Jupiter by July 4, 2016. Only two course corrections are scheduled for the entire mission, and the first of them took place yesterday.

The engine burn began at 6:57 pm EDT (2257 GMT), and lasted for 29 minutes and 39 seconds. The Leros-1b main thrusters functioned flawlessly, delivering the necessary impulse to change Juno's velocity by around 344 meters per second (770 miles per hour).

The maneuver consumed no less than 376 kilograms (829 pounds) of fuel, telemetry relayed back to Earth by the spacecraft suggests. The JPL science team says that there is currently no indication that the course correction failed.

“This first and successful main engine burn is the payoff for a lot of hard work and planning by the operations team,” explains Rick Nybakken, who is the Juno project manager at JPL.

“We started detailed preparations for this maneuver earlier this year, and over the last five months we've been characterizing and configuring the spacecraft, primarily in the propulsion and thermal systems,” he adds.

“Over the last two weeks, we have carried out planned events almost every day, including heating tanks, configuring subsystems, uplinking new sequences, turning off the instruments and increasing the spacecraft's spin rate. There is a lot that goes into a main engine burn,” Nybakken concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //