According to a new scientific study, it would appear that some portion of the human junk DNA has the ability to promote the development of some forms of heart disease. The so-called “junk” DNA is in fact the 98 percent of our genetic material that is not directly responsible for coding proteins. When it was first discovered, researchers had no idea what it was useful for, but over the past few years scientific progress has begun unraveling its mysteries. The latest finding is a part of these ongoing efforts. Researchers found that removing a non-coding region of the junk DNA promotes the narrowing of arteries in mice models, thus paving the way for a host of heart diseases, Nature News reports.

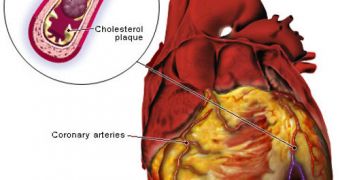

This line of research is especially important, because many people die on account of various heart conditions that they develop over the years. In the United States alone, about 20 percent of all deaths are caused by coronary artery disease (CAD), which is a condition in which fatty plaques build up inside arteries. This diminishes the supply of blood to the heart, triggering a wide variety of negative side-effects. Because of this, CAD has been the target for many investigations over the past few years. In 2007, a research team found that a non-coding stretch of the chromosome 9p21 was directly linked with the condition, and also revealed that certain single nucleotide mutations in the same region was tied to an increased risk of developing the condition.

The most recent investigation worked with these results, taking them one step further. Researchers decided to test the validity of the previous findings by artificially-engineering mice with that specific chromosome area knocked out. "We were really interested in understanding how this purely non-coding interval leads to CAD, so we thought, 'Let's delete it and see what happens'. We did, and found that the expression of two genes nearly 100,000 base pairs away from the deletion dramatically decreased in mice,” explains the leader of the investigation, Len Pennacchio. The expert is a geneticist at the US Department of Energy's (DOE) Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), in California.

The study also found that a large number of the mice that had their non-coding DNA knocked out tended to die earlier than their unaltered comrades. In addition, many of the rodents in the test group also exhibited a tendency towards developing tumors. “How this translates into humans, we don't know yet,” Pennacchio reveals, saying that a lot more work on this lead is required before a final conclusion can be drawn. “This study brings the understanding of 9p21 and CAD risk to another level,” University of Ottawa Heart Institute cardiovascular expert Ruth McPherson says. She was not involved in the study, but conducted a genome-wide association study on CAD on her own. Details of the latest study appear in the February 21 online issue of the esteemed publication Nature.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //