NASA investigators at the agency's Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) determined that the tsunami produced by the March 2011 Tohoku earthquake was able to dislodge large icebergs from Antarctica.

The magnitude-9.0 earthquake struck Japan on March 11, causing widespread damage to both population and infrastructure. The large tsunami the tremor unleashed managed to travel all the way to another hemisphere, and cause glaciers in Antarctica to separate from their ice shelves.

This study marks the first time the direct effects of a large tsunami are shown to remain powerful at such a great distance. The glacier observations were made as part of a routine session by the MODerate Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument, aboard the Aqua and Terra satellites.

Additional observations were also conducted with the advanced instrument suite aboard the European Space Agency's (ESA) Envisat satellites. Researchers were lucky to catch a break while studying the Antarctic, since the area of interest is covered with clouds almost at all times.

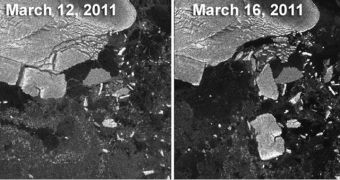

The Sulzberger Ice Shelf was severely affected by the tsunami, as the image attached to this article demonstrates. Even after traveling across the Pacific Ocean, the waves still had enough punch to make large glaciers float out in the open water.

GSFC cryosphere specialist Kelly Brunt led the team that conducted the new study. Details of the work were published in the August 8 issue of the Journal of Glaciology. Northwestern University expert Emile Okal and University of Chicago scientist Douglas MacAyeal were a part of the team as well.

According to the researchers, the tsunami took only 18 hours to reach Antarctica, traveling a distance of more than 8,000 miles (13,600 kilometers). When they arrived, the waves were still powerful enough to cause discernible effects on the ice shelves.

An interesting aspect of this study is that the glaciers which came loose hadn't budged from their current position for more than 46 years. “In the past we've had calving events where we've looked for the source,” Brunt explains.

“It's a reverse scenario – we see a calving and we go looking for a source. We knew right away this was one of the biggest events in recent history – we knew there would be enough swell. And this time we had a source,” she adds.

Upon arrival, the tsunami waves were most likely just 30 centimeters high, but this proved sufficiently stressful for the glaciers. A 260-foot (80-meter) thick chunk of ice was the first to come off.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //