On the 21st of August, a new set of rules and regulations related to embryonic stem cell research came into effect in Japan. The new laws leave more leeway for researchers to conduct their experiments, but some voices say that the measures come too late, and that the time the country lost in a field that was once a big source of national pride will not be easily recovered. Other countries have moved way ahead of Japan in this field of research, so it remains to be seen if the new laws will have any effects.

Upon first inspection, the laws that were set in the country in 2001 were fairly permissive. Researchers could use home-grown embryonic stem cell lines, or they could import them. However, there was a catch. The teams conducting such investigations needed to get approval for their studies, from both local institutions and Science Ministry commissions. This was a real stumbling block. In addition, they had to conduct their experiments in separate facilities from teams conducting work on other types of stem cells, Nature News reports.

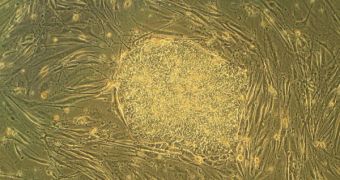

The measures had the effect of costing Japan the leader position in the international stem cell research community. It was, for example, Shinya Yamanaka of Kyoto University who first managed to obtain induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) from differentiated, adult cells, but it soon became obvious to the team that more embryonic stem cell (ES) knowledge was needed before the field could further advance. Therefore, the vast majority of the studies was conducted outside the Asian nation.

Kyoto University (KU) Institute for Frontier Medical Sciences expert Hirofumi Suemori says that even the United States moved ahead of Japan, considering that ES cell regulations in America were much tighter, and federal funding reduced. This was the result of former president George Bush giving in to pressure from right-wing, fundamentalist Christian groups. Even under these conditions, much more ES cell research was done there than in Japan, Suemori says.

The new guidelines, while offering some more leeway, still remain restrictive. One approval step is needed instead of the former two, but the process has remained the same for deriving new stem cells. “I would summarize the change as being from absurd to excessively strict. These irrational guidelines have done and will probably continue to do great damage to all related research fields in Japan,” Norio Nakatsuji, who is the director of the KU Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences, explains.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //