The massive tremor that struck the Asian island nation of Japan this spring was arguably one of the first ever whose effects were captured on radar. Investigators in both Japan and California watched the ripples produced by the massive tsunami as they spread across the Pacific Ocean.

Just a few days ago, scientists published a study showing that less than 18 hours after the event took place, the wave front had already made it across the ocean, to Antarctica. Satellite images obtained via a lucky twist of fate revealed large chunks of ice coming loose from their sheets.

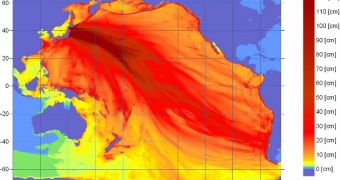

At the same time, geologists were keeping track of how the waves were heading for North and South America. California, a part of Western Canada, Mexico, Peru and Chile were the areas most at risk, so experts kept a close eye on how wave height varied.

Researchers who were in charge of monitoring the tsunami using radio equipment say that this approach may be used as the basis of a new early warning systems, meant to give the population a longer warning period than currently possible.

The Tohoku earthquake registered a magnitude of 9.0 degrees, and produced a massive tsunami of the northeastern coasts of Japan. It caused widespread loss of life and property, and gave rise to the worst nuclear crisis since the 1986 Chernobyl disaster.

One of the main reasons why this event caused so widespread damage was that the country is located at the intersection of four tectonic plates, each of which is going its own way. Collisions between them are inevitable. The last major tremor to affect Japan took place in 1995.

A new early-warning system “could be really useful in areas such as southeast Asia where there are huge areas of shallow continental shelf,” University of California in Davis (UCD) oceanographer and study team member John Largier explains.

He and his group have been involved in studying the ocean with the help of high-frequency radar arrays for about a decade. The vast amount of experience the team accumulated could easily be translated into useful warning technologies.

Details of the readings they collected on the March 11 tsunami were published in the August issue of the esteemed scientific journal Remote Sensing, LiveScience reports.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //