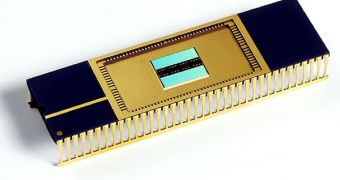

The phase-change memory (PCRAM), also known as chalcogenide RAM or C-RAM is thought to be a viable alternative to the nowadays' non-volatile, memory-based technologies such as NAND flash. The NAND memory prices have dramatically dropped lately, but this type of memory is still expensive and has its limitations.

Intel has just announced a new approach at producing phase-change memory, that would double the storage capacity of a single memory cell. The new process is extremely easy to implement in the already existing manufacturing infrastructure, so companies would not need to change their production gear in order to deliver the new phase-change memory.

Unlike flash and random-access memory, the phase-change memory does not use electrons to store data, but instead, it uses the material's native physical state and atoms arrangement. Before the new achievement, the phase-change memory was designed to work with two states: the atoms could be either loosely organized (amorphous) or caught into a rigid structure (crystalline).

Intel engineers, however, demonstrated that the matter has two extra states, apart from amorphous and crystalline, and these additional states can be used to store data. Intel teamed up with ST Microelectronics and created a new material based on common glass (GST) that has its physics state controlled by heat. The material can be more or less heated up by a built-in miniaturized heater. It can heat the material so it reaches all the four states.

"We can do this successfully with a reasonably sized array, and do it at speeds that are commercially viable," said Intel's chief technology officer, Justin Rattner.

Intel and ST Microelectronics managed to add two bits on a single cell, thus doubling the memory density, since it could previously store a single bit per cell. This allows phase-change memory to compete against today's flash technology. "It's rather important to develop this multi-bit storage technology," said H.-S. Philip Wong, professor of electrical engineering at Stanford University. "If you can't do it, then you're disadvantaged by a factor of two."

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //