The worrying conclusions of a new investigation carried out on animal models reveal that the immune system may in fact attack adult cells that have been reprogrammed into stem cells from a mouse' own tissues. This finding may have serious implications for regenerative medicine.

This relatively-new field of research deals with developing ways of taking adult cells from a patient's body, reprogramming them as stem cells, and then using them for a wide array of therapies.

The entire point of such research is to circumvent compatibility issues, such as those arising when a person receives an organ from another individual. The former need to take immunosuppressive drugs to ensure that their bodies do not reject the transplant.

By using that patient's own cells as a starting point, experts were hoping to circumvent this issue, as the immune system should have theoretically recognized the stem cells as part of the body. But the new study demonstrates that this is not always the case.

The research demonstrated on mice that the immune system can sometimes be activated in response to the injection of reprogrammed stem cells into the body. Until now, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) were considered to be among the most promising types of stem cells out there.

“The iPS cell phenomenon is so new and so hyped up that it’s good we’re taking a step back to ask what they can really do,” comments Stanford University biologist Chad Tang, who was not a part of this study.

The new research, which is published in the May 13 online issue of the top scientific journal Nature, was conducted by investigators at the University of California in San Diego (UCSD), Science News reports.

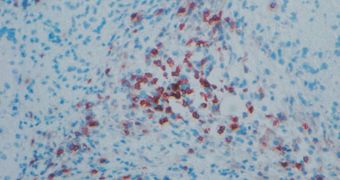

During their experiments on genetically identical mice, the researchers learned that introducing iPSC derived from the rodents' own bodies caused the same type of immune system response that is produced when a foreign organ is transplanted.

In the journal entry, the team explains that iPSC created using reprogrammed viruses elicited a much stronger immune response than those produced via a virus-free approach. This indicates that scientists should now focus their attention on the latter method.

The iPSC the UCSD team used were derived from skin cells, and they were mostly attacked by killer T cells. In future studies, experts will try to determine whether stem cells reprogrammed from other types of adult cells elicit the same effect, and also if the same immune cells conduct the attack.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //