A team of astronomers announced a new theory seeking to explain the interesting equatorial ridge that sets the Saturnine moon Iapetus apart from the crow. Speaking at a conference yesterday, December 15, experts said that an impact with a mini-moon around the space body may have been responsible.

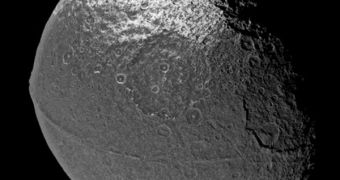

In all fairness, Iapetus is indeed shaped lake a walnut. Its equatorial region features a tremendously large ridge, which is on average about two times taller as Mount Everest. Until now, experts have been at a loss to explain how the feature developed.

The explanation proposed yesterday in San Francisco is very complex, but it also makes a lot of sense, considering that it explains a variety of traits pertaining to the structure and shape of the ridge.

According to the work, the Saturnine moon's own gravity is responsible for the creation of the structure, starting many millions of years ago. In the past, Iapetus may have had a moon of its own.

Planetary scientists now believe that, at one point in its history, it was battered by space impactor, which nearly destroyed the moon, and ejected a lot of material from its surface.

A good analog for this is the events that took place when the Moon appeared around the Earth. Two Mars-sized objects collided, and the result was a planet and a smaller body orbiting it.

Similarly, following the impact that affected Iapetus, a mini-moon was formed around it. But, unlike the Earth-Moon system, that body was slowly but surely destroyed by its host's gravitational pull.

The space rock – which coalesced from debris ejected by the Saturnine moon – was ripped apart piece by piece, and all these chunks of rock began depositing on Iapetus' surface.

According to the new theory, as the mini-moon was consumed, the equatorial ridge grew until there was nothing more to accrete. This helps explain that structure's shape and location.

“Imagine all of these particles coming down horizontally across the equatorial surface at about 400 meters per second, the speed of a rifle bullet,” explains William McKinnon.

“Particles would impact one by one, over and over again on the equatorial line. At first the debris would have made holes to form a groove that eventually filled up,” the scientist adds.

McKinnon holds an appointment at the Washington University in St. Louis (WUSL), and is also the co-author of the new study, which was presented at the 2010 annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

“It's one of the most astounding features in the solar system. It kind of gives Iapetus the appearance of a giant space walnut,” added University of Illinois-Chicago expert and lead study author Andrew Dombard,” quoted by Space.

The science team is currently developing a computer model to test the predictions in their model.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //