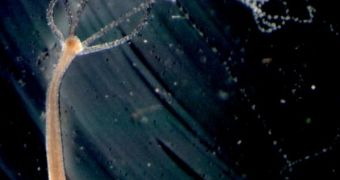

A group of American researchers from the University of California in Santa Barbara (UCSB) has recently made huge progress in understanding how vision in higher animals, including humans, developed. The experts looked at a member of an ancient group of sea creatures, called the hydra, in order to gain some more insight into how photosensitivity and the ability to convert electrical signals into vision developed. Details of the work are published in the British scientific journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, ScienceDaily reports.

The phylum cnidaria, which includes hydra and the more commonly known jellyfish, are creatures that first emerged more than 600 million years ago, predating most known life forms. During the investigation, “We determined which genetic 'gateway,' or ion channel, in the hydra is involved in light sensitivity. This is the same gateway that is used in human vision,” UCSB Department of Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology Assistant Professor Todd H. Oakley explains. The investigator was also the senior author of the journal entry.

The gateway of vision is in fact dictated by a gene controlling the entrance and exit of ions from a certain type of ion channels. These channels are involved in starting the cascade of electrical signals that eventually gets propagated all the way to the visual cortex, where they are converted into the sensation of sight. The gene called opsin plays a crucial part in this, especially in vertebrates. It allows for a different type of sight from creatures such as flies, for example. Apparently, the hydra and the vertebrates have more in common as far as vision goes than the hydra and the flies. Insects developed their way of seeing later than higher animals did.

“This work picks up on earlier studies of the hydra in my lab, and continues to challenge the misunderstanding that evolution represents a ladder-like march of progress, with humans at the pinnacle. Instead, it illustrates how all organisms – humans included – are a complex mix of ancient and new characteristics,” Oakley says of the investigation. Other contributors to the research include UCSB undergraduate Caitlin R. Fong, the second author of the paper, and David Plachetzki, who is now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California in Davis (UCD).

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //