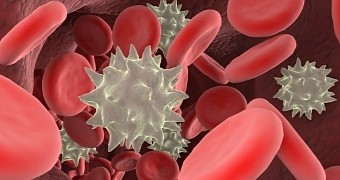

In a series of laboratory-based experiments, scientists-turned-hypnotists managed to force human skin cells to forget all about their past lives and become white blood cells ready and willing to join the immune system's troops and fight potential threats.

These experiments, detailed in the journal Stem Cells, could lead to the development of better treatment options for cancer and other conditions caused by the presence of so-called invaders in the body.

A little genetic manipulation goes a long way

Specialist Ignacio Sancho-Martinez with research organization the Salk Institute explains that, in order to get the human skin cells to become white blood cells, he and his colleagues first exposed them to a molecule dubbed SOX2.

This molecule gave the human skin cells amnesia. Simply put, SOX2 caused them to forget what they were and become rather confused about their identity, the scientists explain in their paper in the journal Stem Cells.

Later on, the cells were introduced to a genetic factor known as miRNA125b. Having come into contact with this genetic factor, the former human skin cells became fully functional white blood cells, Phys Org informs.

“We tell skin cells to forget what they are and become what we tell them to be – in this case, white blood cells,” says Ignacio Sancho-Martinez. Furthermore, “Only two biological molecules are needed to induce such cellular memory loss and to direct a new cell fate.”

It's important to note that SOX2 does not reverse the cells all the way back to an embryonic-like state, when they were not yet differentiated, and instead only rewinds them up to the point where they can respond to the presence of miRNA125b and become white blood cells.

What's next?

The Salk Institute scientists say that, for the time being, they are not ready to move on to carrying out clinical trials involving human patients. However, they argue that the outcome of their laboratory-based experiments is nothing short of encouraging, and that it is only a matter of time until their work could benefit people.

More so given the fact that, when compared to the practice of growing new types of cells from induced pluripotent stem cells, this method described in the journal Stem Cells is faster (2 months vs. 2 weeks) and less likely to encourage the development of tumors.

“It circumvents long-standing obstacles that have plagued the reprogramming of human cells for therapeutic and regenerative purposes,” explains study senior author Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, holder of Salk Institute's Roger Guillemin Chair.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //