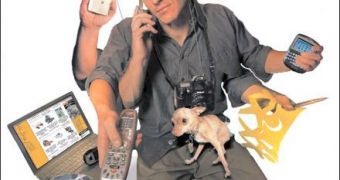

A new research advises us not to trust the legend of our multitasking, since we're not at all able to do more things at the same time consciously.

The same study stresses on the emergence of an adjacent unique ability that propelled us to an evolutionary edge - the humans' capacity of toggling their attention between different tasks extremely fast. Sure, technology may enable us to address more operations at any given time, but this doesn't mean that our consciousness is able to focus on each of them simultaneously.

In order to explain how this works, scientists point to the activities of a known case of a so-called multitasking endeavor: being a chef in a restaurant. This implies tracking orders and the way they are carried out, managing food preparation and serving the meals. This is especially hard for short-order cooks. Clients also seem multitasking when issuing their verbal orders, and sometimes, among egg cracking, pancake flipping, coffee cups refills, potato frying and working on the counter, there's about half a dozen of more complicated orders to keep track of. Also, when talking on the phone while driving and listening to the radio simultaneously to paying attention to the traffic and the road, researchers are confident that these activities are done in order, not at the same time.

“People can't multitask very well, and when people say they can, they're deluding themselves. The brain is very good at deluding itself,” claims neuroscientist Earl Miller, a Picower professor of neuroscience from the MIT. He backs this claim up by revealing that the tasks we're carrying compete in using the same part of our brain, “Think about writing an e-mail and talking on the phone at the same time. Those things are nearly impossible to do at the same time. You cannot focus on one while doing the other. That's because of what's called interference between the two tasks. They both involve communicating via speech or the written word, and so there's a lot of conflict between the two of them”.

Daniel Weissman, a neuroscientist in charge of an experiment developed at the University of Michigan used an MRI to observe the neural activity of test subjects who were required to give increasingly fast answers to colored number-related problems. “If the two digits are one color - say, red - the subject decides which digit is numerically larger. On the other hand, if the digits are a different color - say green - then the subject decides which digit is actually printed in a larger font size.” While this seemed rather easy in the beginning, when the display speed of the numbers increased, the test proved its difficulty. The brain has to pause and dump the previously collected and analyzed information in order to focus on the current one. When it is presented the green numbers, it must first lay aside the data referring to the red ones, process the operation manner related to the green ones and only then act accordingly.

“If I'm out on a street corner and I'm looking for one friend who's wearing a red scarf, I might be able to pick out that friend,” explains Weissman. "But if I'm looking for a friend who's wearing a red scarf on one street corner, and in the middle of the street I'm looking for another friend who's wearing a blue scarf - and on the other side of the street I'm looking for a friend wearing a green scarf - at some point, I can only divide my attention so much, and I begin to have trouble."

Still, humans show an increased activity of their frontal lobes' executive systems, which separates them from the rest of the Earth's animals, translating into their being able to monitor several things with very small lags, even though not at the same time. It's this keeping track of things at high rates that allowed humans to become the dominant species on the planet and give them the upper hand when hunting larger, ferocious species.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //