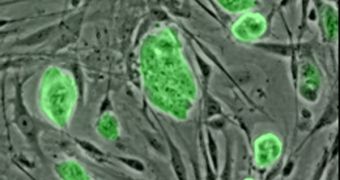

Two teams of researchers from the UK and Canada have discovered a new way of obtaining stem cells from nothing more than regular skin cells, and a few genes, which they manipulate so as to trigger the desired change in the cells. After the process, the obtained structural units behave exactly like embryonic stem ones, which means that they can be turned into any type of tissue geneticists want. This breakthrough may be the key to advancing stem cell research further, as most critics to this genetic method are against it because it obtains its cells from viable human embryos.

The new way of modifying skin cells results in pluripotent stem ones (iPS cells), which many see as an acceptable alternative to other stem cells. Until now, the main problem with this type of structural units has been that researchers had to use a virus in order to “turn” them, a process that had a major drawback – the virus usually transcribed its own genetic information into the DNA of the host cell. If these cells had been inserted into a living animal or a human, they would have triggered rare forms of cancer.

In their paper published in the latest online edition of the journal Nature, the two teams say that the method they have devised prevents such risks, thus making this alternative highly feasible. “It is a step toward the practical use of reprogrammed cells in medicine, perhaps even eliminating the need for human embryos as a source of stem cells,” Medical Research Council (MRC) researcher Keisuke Kaji, from the Center for Regenerative Medicine in Edinburgh, explains.

“Combining this work with that of other scientists working on stem cell differentiation, there is hope that the promise of regenerative medicine could soon be met,” MRC Center head Ian Wilmut, who was part of the team of scientists that cloned the first mammal, Dolly the sheep, adds. Still, he cautions that the wide-scale implementation of this method is still some years away, but that its existence can even now be saluted as an important step in this field.

Parkinson's disease, diabetes, cancer and spinal cord injuries, as well as other serious medical conditions could be cured in the future by using the new technique. Physicians know that regenerative medicine is key to potentially even replacing entire organs, without the receivers of the transplants running the risk of having their bodies reject the new “parts.”

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //