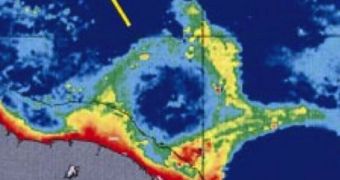

In a new study, experts found massive currents of water affecting the coasts of Brazil, in South America. The formations, resembling giant Frisbees as seen from satellite, are produced by the interactions of larger, already-known currents passing through the area.

According to experts, these disks of water influence ship traffic to a great extent, causing a surge in travel costs. They also affect local climate patterns to a significant extent, the team adds.

Satellite data indicate that the warm North Brazil Current is primarily responsible for the production of these smaller formations. This current flows along the northeastern coasts of Brazil, following a northward direction.

Its most important contributor is the South Equatorial Current and the Amazon River. The latter has an east-to-west flow, and is located roughly between the Tropic of Capricorn and the planet's Equator.

This interplay of factors is feeding vast amounts of nutrients to areas located immediately north of the Equator. However, its flow is also affected by strong winds coming from the northwestern parts of the country, LiveScience reports.

These winds force a part of the waters in the North Brazil Current to flow parallel to the Equator, heading east. At times, when the air movements are really strong, the separated waters take such a sharp turn that they begin to loop.

This forms the huge water discs, which are visible from orbit. The smaller currents begin to move across the surface of the Atlantic while still swirling, in a flying Frisbee-like motion.

Though researchers knew about the existence of such current rings for years, they had no way of finding out all details about some of their most important characteristics. These include rate of spin, speed, depth and overall size.

In the new research, experts used a neural network – a brain-like construct – to peer over months-worth of data, and pick out patterns. The formations were found to be bigger, faster and taller than believed.

According to University of Miami physical oceanographer William Johns, these eddies are the biggest-ever that form in the world's oceans. Their diameter can reach up to 250 miles (400 kilometers).

“They have a huge effect on navigation. If ships were aware of them, they could probably save considerable money on fuel by using them to their advantage,” the expert explains.

In a paper published in the January 11 online issue of the Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans, the expert and his group say that the eddies also influence climate, both locally and globally.

The heat they carry is moved further northwards than usual, and it eventually ends up in the Gulf Stream system. This current releases the heat in the Northern Atlantic, and the warm air then moves over Europe, determining climate patterns here.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //