For paleontologists studying lost forms of life, making the difference between males and females of the same species and individuals from closely related species is crucial in understanding them.

In living animals, the genitalia, that differs between males and females, are the surest way to assess the sex of an individual. But these are soft tissues that do not mark the skeleton to be traced in fossil remains. However, there are some bony traits associated with reproduction that can give a clue about the sex of the individual.

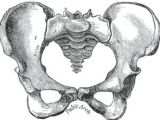

In the woman pelvis (image2), the angle of the bony Arch under the pubis is much larger than it is in men (image 3) and the sacrum is more widened as well, traits linked to a bigger pelvic outlet that enables women to give birth.

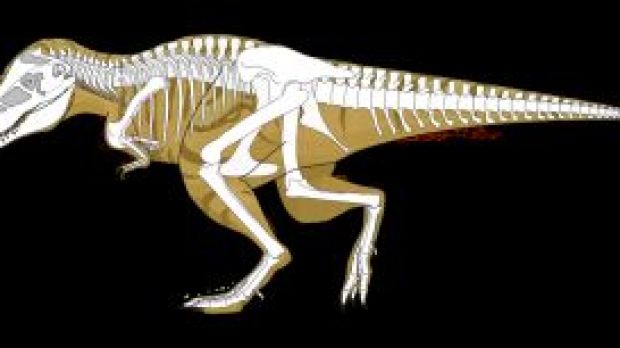

In the same way, researchers can make the difference in the dinosaur Tyrannosaurus rex (image 1), which exhibits a trait found in crocodiles (crocodiles and birds are the closest relatives of the dinosaurs): females have pubic bones with a higher angle, a trait that ensures additional abdominal room to ease the passing of eggs.

Moreover, the second chevron bone (these are V-shaped bones beneath each tail vertebra) in female T. rex is much larger than the first chevron bone, while in males they are equally sized, exactly like in crocodiles, an adaptation for assisting egg-hatching.

In the polygamous species (a male mates with several females, or, less commonly, a female with more males, situation called polyandry), the task of sex identification is even easier, as usually there is a pronounced sexual dimorphism (males and females display high differences in their body form, named secondary sexual traits).

Secondary sexual traits are linked with competition between males for access to females.

Secondary sexual traits are, besides the size, the lion's mane, the cheek pads of male orangutans, antlers and horns of male deer and antelopes; or feather ornamentation in many male birds like the peacock or paradise birds. (As some dinosaurs were feathered, they may have displayed this type of sexual dimorphism).

In many duck billed dinosaurs and pterosaurs (flying reptiles from the dinosaur era), males presented elaborated crests, which initially made researchers place them in different species from females.

The size as a sexual dimorphism is highly employed by paleontologists: there must be a bimodal distribution, males clustering around a large variant and females in the more diminutive one.

But it is difficult to establish the sex of skeletons of large females and small males, if only this criterion is taken in account.

The bimodal distribution revealed that the early hominid Australopithecus afarensis, with its most known individual being the famous Lucy, is just one species, and the two size clusters only depicts males and females.

This also points to a highly polygamous species.

Studying the skeletons of Tyrannosaurus rex, researchers found that females were larger than males, thus the species was either polyandrous (like seen today in button quails and some shore birds, where large females combat between them for males) or formed pairs like in modern bird prey (eagles and hawks) where the female is larger than the male.

On the other hand, on a Belgian site, the researchers discovered the remains of 39 individuals of the dinosaur Iguanodon that presented the same size bimodal distribution, but correlated with anatomical differences in the skull, hand, foot and pelvis larger than what usually depicts one species.

That's why researchers described two distinct species, I. bernissartensis and I. mantelli, but a puzzle remains: how two closely related dinosaurs could ecologically inhabit the same area.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //