University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA) experts announce the discovery of a new method for amplifying the actions of killer T cells, a type of immune system cell that plays a critical role in destroying infectious agents in the human body.

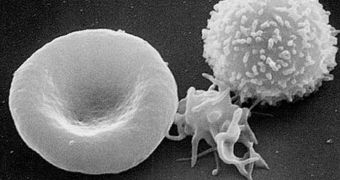

A specific subset, called CD8 cells, can have their function boosted for a long period of time when scientists stimulate the innate immune system response every person has. This avoids the necessity of using foreign substance for the job.

Once made more active, these cells can multiply easier and at higher speeds, and can expand to numerous areas of the body, where they are needed. An immune system amped up to this state can easily fight melanoma, a type of common skin cancer.

The new study was carried out by experts based at the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center (JCCC), who are renowned for their groundbreaking work in understanding cancer and its causes.

In experiments aimed at assessing the efficiency of the new technique, the researchers noticed that mouse models who had metastatic melanoma – spread all the way to the brain – were a lot more capable to fight back against the infection.

Utilizing this approach in humans would make the tumors more susceptible to the actions of cancer-killing, experimental immunotherapies that are currently being developed at various universities.

Deadly glioblastoma and metastatic melanoma are two of the most complex-to-treat forms of cancer, but the new approach could address them both, experts at the JCCC believe. They add that ramped up killer T cells are more efficient at identifying, and binding to, tumor sites.

One of the hugest fails of the immune system occurs when these cells are unable to find the cancer cells, and walk right past them. This is what generally happens, and experts have to compensate for this oversight with medication and radiation therapy.

Further details of the study were recently published in the May issue of the peer-reviewed Journal of Immunology. The senior author of the work was JCCC scientist and UCLA associate professor of neurosurgery Robert Prins.

“We wanted to see if we could make these cells become better at either recognizing the tumor or killing tumor cells,” explains UCLA graduate student and first study author Dominique Lisiero.

“We didn't know what to expect, but what we found was that when we programmed these cells in the presence of IL-12 (interleukin 12 proteins), the tumors decreased in size and the mice with brain metastases survived longer,” she concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //