Terra-forming is a process described in the Sci-Fi books as the modification of a planet's features, so as to better accommodate human life. Apparently, that's what several large corporations are trying to do in the Southern Ocean, where they say that the large stretches of water could be an enormous source of revenues, if they could be converted into more efficient carbon sinks. They aim at spraying trace amounts of iron and other nutrients over the seas, in an attempt to make them “flourish.”

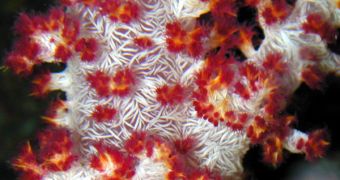

Research conducted over the last decade, in various parts of the globe, concluded that spraying the ocean surface with very small amounts of iron and other specific substances created an environment suitable for the booming expansion of phytoplankton, the microorganisms responsible for trapping the carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. Once these tiny creatures are dead, they sink to the bottom of the ocean, carrying with them excess carbon as well.

According to some scientists, this process could store as much as 1 billion tonnes of carbon per year, which would constitute a huge portion of the global output registered every year. Companies that manage the enterprises would also benefit from them, as they would be able to sell carbon credits to foreign companies that would have to buy them, in order to avoid being shut down.

Other experts, however, believe that engineering at such a grand scale could have disastrous impacts, and not just because no one has any idea about what will happen if the plan to spray the oceans goes into full effect, but also because the potential changes that the waters would undergo haven't even been pondered upon by anyone. In principle, nothing should go wrong, but scientists who still keep a shred of responsibility urge caution in deciding future long-term plans.

On an international level, states are divided on the matter, and each of them will most likely make its own rules in this respect. International maritime organizations have already urged their members to use the “utmost” caution on the matter, which is pretty much like saying “don't do it.” "It is extremely important to look at the ecological risks of this kind of activity,” says John Cullen, who is a professor of oceanography at the Dalhousie University, in Nova Scotia, Canada.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //