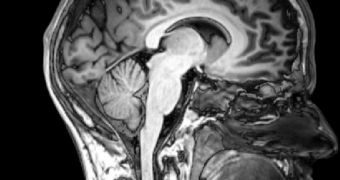

Similar to experts who used the Rosetta Stone to understand Egyptian hieroglyphs more than 200 years ago, scientists at the Carnegie Mellon University are using a number of imaging techniques to understand the complex mechanisms and processes that underlie the human brain. The team combines brain imaging methods and machine learning techniques to get a clear view of how the neural pathways inside our brains make sense of nouns, and arrange them accordingly. The work is enormously difficult, but the group says that progress is slow, but sure.

The new approach to understanding our minds is spearheaded by neuroscientists Marcel Just and Vladimir Cherkassky, working together with computer scientists Tom Mitchell and Sandesh Aryal, all at CMU. One of the main reasons for trying to understand how the brain codes nouns is the fact that this knowledge could lead directly to the development of a host of new treatments for a large number of psychiatric and neurological illnesses, the team says. The researchers compare their research with discovering the beginning of a neural Rosetta Stone.

“In effect, we discovered how the brain's dictionary is organized. It isn't alphabetical or ordered by the sizes of objects or their colors. It's through the three basic features that the brain uses to define common nouns like apartment, hammer and carrot,” Marcel Just, who is the director of the CMU Center for Cognitive Brain Imaging, and also the D.O. Hebb professor of psychology at the university, says. The three features relate to how people physically interact with objects, how the nouns relate to eating, and how they are related to a shelter or enclosure. Full details of the investigation appear in the latest issue of the open-access scientific journal PLoS One.

“Our vocabulary of 60 test nouns lacked any words related to the missing dimension, such as 'spouse' or 'boyfriend' or even 'person.' We certainly expect some human dimension to be part of the brain's coding of nouns, in addition to the three dimensions we found. With psychiatric and neurological illnesses, the meanings of certain concepts are sometimes distorted. These new techniques make it possible to measure those distortions and point toward a way to 'undistort' them. For example, a person with agoraphobia, the fear of open spaces, might have an exaggerated coding of the shelter dimension. A person with autism might have a weaker coding of social contact,” Just concludes.

More details of the work can be found here.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //