University of Alberta investigators have determined in a new study that one of the most important things allowing the human brain to acquire and keep hold of permanent memories is its ability to rehearse and repeat electrical impulses through neurons.

The finding is in tune with discoveries made in past studies, suggesting that repetition may be the main reason why we remember things better after sleeping at night, or taking a nap. The lack of additional stress on memory neurons allows them to retrace their former impulses, consolidating memories.

UA psychology professor Dr. Clayton Dickson says that the process may be very similar to what we do when we try to memorize a phone number, for example. We repeat the numbers again and again, and this eventually allows us to store it, and easily retrieve it when the need arises.

“We repeat the number several times to ourselves, so hopefully we can automatically recall it when needed,” Dickson explains. He was the lead researcher on the new investigation, PsychCentral reports.

With this in mind, it makes sense to think that the neurons involved in memory formation take advantage of any downtime of the brain, such as those occurring during sleep. When these occur, the nerve cells involved in memory formation start firing electrical impulses through the same pathways.

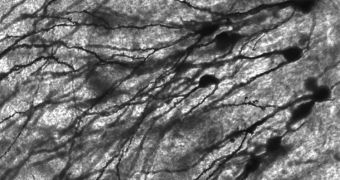

Experts hypothesize that each new memory is contained within a certain succession of neurons. If that is the case, then firing neural impulses through it can lead to a strengthening of synapses connecting the nerve cells, which then contributes to strengthening the memory the pathway contains.

UA experts believe that stronger synapses make for stronger memories. Due to a phenomenon called neural plasticity, synapses cannot strengthen unless electrical signals pass through them back and forth several times.

Neural plasticity is an adaptive trait of the brain, which allows it to become better at certain tasks, while neglecting others. A musician, for example, will develop steady fingers, a keen hearing and great muscle control and coordination, all of which will be produced by stronger synapses between certain neurons.

“Those connections allow the brain to retrieve the memories and rehearsal ensures that they last for a long time. It was previously thought that only biochemical processes like protein synthesis were important for solidifying memories,” Dickson explains.

Additional investigations in this field could lead to the development of methods for deleting negative or post-traumatic memories. This could be of great use to trauma patients, including soldiers returning from the front lines.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //