I guess you already knew that the tinny buzzy devils that transform our nights in real nightmares and transmit fatal diseases like malaria or West Nile fever are guided to our bodies by a GPS that is turned on by the carbon dioxide we exhale.

A team at Rockefeller University has found two proteins in carbon dioxide-sensing neurons in drosophila fruit flies and mosquitoes; further research could help developing better insect repellants to protect us against disease or annoyance.

"Once we show that the mosquito receptors function in the same way as the fly receptors, we take a hint from drug companies--once they have a protein target in mind, [we] can screen for inhibitors of it." says neurogeneticist Leslie Vosshall.

In the carbon dioxide researchers found sensing neurons located in the fruit fly's antennae, two chemosensory receptor proteins Gr21a and Gr63a. "One of them binds to the smell," she says, "and the other one is critically important to make the [binded protein] function."

By removing genetically one of the two proteins, the Rockefeller team found that a combination of the two is necessary to get the antennae neurons functioning. The team investigated the mosquito genome for genes related to those of flies and found two strong candidates: GPRGR22 and GPRGR24. "They are 62 % and 48 % identical, which, in the world of chemosensory receptors, is very similar," Vosshall notes. "There's very little in common between the fruit fly and the mosquito as regards other taste receptors and smell receptors, so these are pretty strongly conserved."

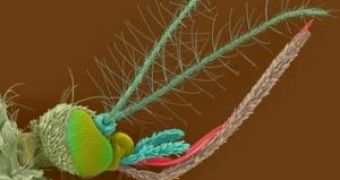

The mosquitoes' carbon dioxide-sensing neurons are in their maxillary palps (specialized sensory organs located on either side of the insect's proboscis, which the female uses to suck blood from her host, blue in the picture). "That's maybe the reason why mosquitoes are attracted to CO2 whereas fruit flies are repelled by it", said Greg Suh, a researcher at the California Institute of Technology.

The team is looking to disable these mosquito receptors by developing an effective repellant. The current standard compound in bug spray is DEET, but its precise action is not known. DEET could be improved by inhibiting GPRGR22 and GPRGR24. "Whatever we devise would need to be safe, cheap & so that it can be used in the developing world," Vosshall says. "They would have to be the kinds of molecules that would sit safely on your skin, but also form a cloud around you and act on the mosquitoes that are about to bite you."

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //