Some plants are known for having both their male and female reproductive organs very close to each other, which favors inbreeding. A new investigation shows how petunias prevent this from happening.

All species have over millions of years of evolution learned the hard way that inbreeding is not a good strategy for producing viable offspring. Harmful genetic mutations cause extensive damage to the young ones, usually killing them very fast.

The same holds true in plants as well. When they need to produce offspring, it's best that they do it by avoiding inbreeding with related plants. Petunia really stands out from the crowd in this sense.

This particular species performs an extremely complicated genetic dance of self-incompatibility when trying to multiply, which in turn ensures that it avoids inbreeding.

A new investigation into this ability was conducted by researchers at the Penn State University, who were led by Teh-hui Kao. They worked closely with colleagues at the Nara Institute of Science and Technology in Japan, who were led by professor Seiji Takayama.

The group published its findings in the November 5 issue of the top journal Science. Funds for the investigation were provided by the US National Science Foundation (NSF).

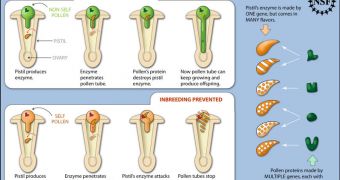

One of the main conclusions in the research was that petunias have an inbreeding-protection system that works similarly to the response immune systems give to invading pathogens.

The plant's secret is in its pollen proteins, which are not encoded by the same gene. Rather, the petunias contain a large variety of related genes, each of which encodes pollen proteins.

These proteins have to withstand the attack of enzymes in the pistil, and only the molecules that are genetically different from the cells in this structure can survive. The other proteins, which may contribute to inbreeding, are destroyed in the process.

“The more I get to know this system, the more I respect plants. They have a truly sophisticated system to prevent inbreeding!” explains Kao, who has spent more than 20 years studying these plants.

In animals, inbreeding is oftentimes avoided in large populations, and is already a part of mammals' instincts. In humans, it is punishable by law, and is not socially excepted in most parts of the world.

Offspring produced through inbreeding are more prone to be weak and sickly, as evidenced by the kids of royalty in old Europe. Many of them suffered from weird genetic diseases, and were hindered by this throughout their lives.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //