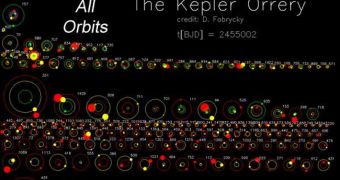

Over the past two decades or so, astronomers uncovered more than 550 extrasolar planets from the ground. After NASA launched its Kepler Telescope, an additional 1,235 were discovered all over the place. But none of the identified, multiple-transit system is like our own.

Researchers say that one of the things which make our 8-planet system unique is that fact that our neighboring planets exhibit a tilt from the Sun's plane. This is very interesting, since it makes some of these objects invisible to alien astronomers.

Some orbits, such as those of Mercury and Venus, are tilted by up to 7 degrees, which means that there is a very slim possibility extraterrestrials would be able to observe them using telescopes. But this was not observed in other solar systems.

Interestingly, as researchers were trying to find more exoplanets, they weren't expecting to discover many multiple-transit ones. These are systems which feature several exoplanets around a star.

At the beginning of the survey, astronomers were expecting to find only a handful of such systems. But, as it turns out, they are more common in the Milky Way than we thought. As such, it would appear that this configuration is not as unique to our own solar system as thought.

Of the 1,235 extrasolar planets Kepler found, 408 were discovered in such configurations. The most important thing to note here is that none of these objects have orbits that are tilted from the star system's plane, Space reports.

“We didn't anticipate that we would find so many multiple-transit systems. We thought we might see two or three. Instead, we found more than 100,” explained Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) astronomer David Latham.

The investigator also presented the findings of his team's new study on Monday, May 23, at the 218th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), which was held in Boston, Massachusetts.

One of the explanations the CfA team proposes for why there is no tilt among those exoplanets is that the systems in which they orbit lack Jupiter-sized gas giants. Only such massive objects can produce the necessary gravitational interferences to modify the orbits of other planets.

“Jupiters are the 800-pound gorillas stirring things up during the early history of these systems. Other studies have found plenty of systems with big planets, but they’re not flat,” Latham explained.

“These planets are pulling and pushing on each other, and we can measure that. Dozens of the systems Kepler found show signs of transit timing variations,” CfA astronomer Matthew Holman adds.

These observations will be confirmed or denied by future datasets Kepler provides. The telescope found all those exoplanets in just four months of operations, and its mission is only beginning.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //