A team of scientist that published a new opinion piece in the March 27 issue of the journal mBio argues that the Black Queen Hypothesis (BQH) helps explain why some microbes continue to live and multiply even when they lose an ability that is considered to be critical for their survival.

Instances of this happening have been observed several times, both in the lab and in the wild, and scientists have always been interested in learning how survival is possible for microorganisms under these circumstances. The new paper proposes a potential solution.

It could be that some microbes shed functions necessary for their very survival, the authors write, but they do not do so without a back-up plan. Most often, these critical functions are lost only after the organisms have been made part of larger structures and communities.

In other words, it could be that losing their ability to perform critical tasks is forcing them to cooperate with each other, helping them become more organized, and increasing their chances for success.

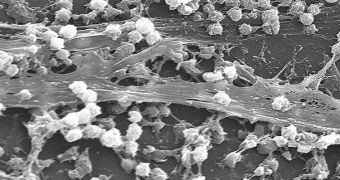

Lately, cooperative microbial or bacterial communities have begun emerging, experts say. This is painfully obvious in hospital infection rates, and in the number of people who die because of them, Astrobiology Magazine reports.

Bacteria such as the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) have learned to create biofilms that are impenetrable for antibiotics. Each individual organism in the biofilm relies on the others to hold down the fort and survive.

The new paper proposing the BQH was authored by Michigan State University (MSU) scientists Richard Lenski and J. Jeffrey Morris, who worked closely with colleague Erik Zinser, at the University of Tennessee.

“It's a sweeping hypothesis for how free-living microorganisms evolve to become dependent on each other. The heart of the hypothesis is that many genetic functions provide products that leak in and out of cells and hence become public goods,” Harvard University expert Richard Losick comments.

He was not a part of the team that wrote the paper, but was responsible for editing it before publication.

“I have a special interest in how bacteria form biofilms, complex natural communities that often consist of many different kinds of bacteria. The Black Queen Hypothesis provides a valuable new way to think about how the members of these abiofilm communities coevolved,” Losick concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //