Experts warn that some exoplanetary studies could reveal false-positive results, in the sense that they may indicate a world to be habitable, when in fact it is not. Responsible for these erroneous readings may be meteorites bouncing through the atmospheres surrounding these alien worlds.

The space rocks may contribute significant volumes of organic gases such as methane to these atmospheres, making it look as though alien organisms produced it. From so far away, it would be rather difficult to tell the difference.

This is especially true for a class of meteorites known as carbonaceous chondrites. They are known to have brought volatile elements, such as nitrogen, carbon and hydrogen to our planet early on in its history. They may have also contributed some organic material.

One theory, called panspermia, holds that meteorites and comets are responsible for seeding both water and life here on Earth, bringing it from elsewhere in space. Studies suggest that the chemical precursors of life can be found throughout all galaxies.

Warnings such as this one are very important, considering the large number of exoplanets confirmed to date (more than 770) and the ones still awaiting confirmation (in excess of 2,300). Most of these worlds were discovered using the NASA Kepler Telescope.

Temptations to announce the discovery of alien life may be too strong for some scientists to ignore. If, for example, a world is found inside its parent star's habitable zone, where liquid water can endure, and methane is detected in its atmosphere, one could argue that microbes are alive on that planet.

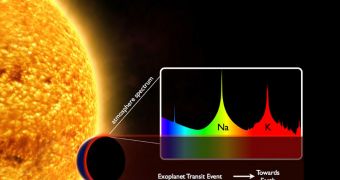

“This could pose a problem, since the search for life on these exoplanets is dependent on remote observations such as spectroscopic analysis of their atmospheres, as had been used to detect the methane in the atmosphere of Mars,” researcher Richard Court explains.

“There is no chance of spacecraft physically visiting these exoplanets many light years away in the foreseeable future,” adds the expert, who is a planetary geologist at Imperial College London (ICL).

The scientist and his team published the results of their new analysis in the September 6 online issue of the esteemed scientific journal Planetary and Space Science, Astrobiology Magazine reports.

The group proposes that future investigations of exoplanetary atmospheres be concentrated on oxygen, a chemical that is too reactive to remain airborne for extended periods of time without something producing it. On Earth, that something is trees.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //