Experts have always thought that lower atmospheric temperatures help keep glaciers frozen in ice sheets, or on mountaintops, but new measurements from a NASA satellite show that ice spreads play a crucial role in keeping temperatures low. Greenland is especially important in this scheme, as its ices reflect back a large amount of the incoming solar radiation, which, in turn, helps keep the arctic shelves cool and frozen. The fact that Greenland's ices are melting thus gains new significance, considering that they are the “guardians” of the North Pole ice sheet.

The thing about ice sheets is that, once they start melting, they enter a vicious circle that cannot be easily stopped. White ices reflect light, but, as they melt, they produce “black water,” which is darker than the average color of the ocean. When stricken by light, it absorbs more of its energy, thus getting warmer than oceanic water usually does. Because they are located near the glaciers, the warming waters cause more ice to melt, thus fueling the vicious circle. While this may stand up for the areas near the ocean, the ice sheets on Greenland's main land remain frozen throughout the year, reflecting back more solar radiation than any other patch of land or sea at the same latitude.

The NASA Langley Research Center's Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy Project supplied the CERES FLASHFlux data that was required to compile the new images. The CERES experiment is one of the highest priority scientific satellite instruments developed for the American space agency's Earth-Observing System (EOS). Both the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) and the EOS Terra satellites contain instruments belonging to Clouds and the Earth's Radiant Energy System (CERES).

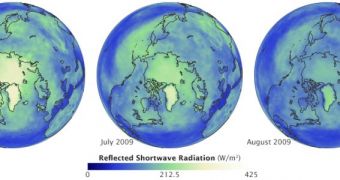

During the summer, the amount of solar radiation that hits the pole should trigger higher temperatures than it does in reality. The difference is precisely represented by the light reflected back into space by the ice sheets. The color white is known to reflect most wavelengths, whereas black captures them most effectively. “The globes [images] show the amount of incoming sunlight (watts per square meter) reflected by Earth in June, July, and August 2009, based on measurements collected by the CERES sensor on NASA’s Terra satellite,” a press release on NASA's Earth Observatory website says.

“Clouds over the North Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans and bright land surfaces, such as the Sahara Desert of North Africa (bottom right edge of globes), continue to reflect a significant amount of sunlight into late summer,” it concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //