One of the most difficult things for scientists, philosophers and laymen alike to do is provide accurate and uncontroversial definitions for some of the most common words we use. Two of these words are “space” and “time.” Even though we use them every single day, there is no clear consensus on what they represent. Albert Einstein, for example, defined time as something you read on a clock. His definition is one in many. For centuries, philosophers have attempted to determine how we perceive the two concepts, but their studies were not too successful, AlphaGalileo reports.

A new investigation, however, proved that at least in the minds of children space and time are inseparable. The findings do not necessarily apply to adults, but the researchers behind the study say that there is no doubt in their mind that kids relate time to space. Still, the opposite is not necessarily true. Even in the general population, the concepts are intertwined inside our thoughts, as countless previous studies have shown. The conclusion of the recent survey that was conducted on children is detailed in the April issue of the respected scientific journal Cognitive Science.

Another interesting result of the investigation showed that time and space, in the minds of children, are asymmetrically separable. What this means is that kids have the ability to think of space independent of time. However, it has become clear in the new research that they cannot conceptualize time as a function independent of space. The researchers were surprised to learn about the events taking place in the mind of children, considering that, in the real-world, the two are thought to be inseparable altogether.

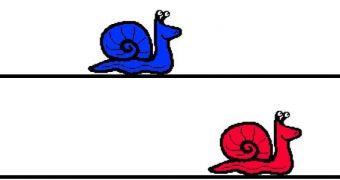

The new investigation was conducted by a team of researchers based at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, who were led by expert Daniel Casasanto. The group collaborated closely with colleagues based at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in Greece, and also the Stanford University, in the United States. During the experiments, children were asked to watch animated videos of races between snails, each of the animals located on its own track. The races went on over various distances and durations, and the children were then asked to tell researchers the distance each had traveled.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //