Investigators at the Brown University say that carbon nanotubes (CNT) can interact with living cells in a negative manner, harming the latter. This research is part of a wider effort meant to gage the influence of nanotechnology on living organisms.

In addition to CNT, other long, nanoscale materials cause the same type of harm, the team explains. Scientists say that cells consider these artificial structures to be sphere, and therefore try to engulf them. This process is irreversible, and the cells can never fully engulf a long nanotube.

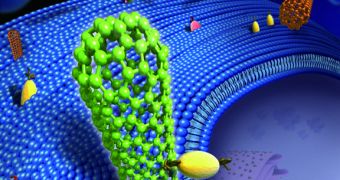

As evidenced by the image attached to this article, one end of the CNT is constantly sticking out of the cellular membrane, impeding it from completing its natural functions. The Brown team covered the interactions between cells and CNT, gold nanowires and asbestos fibers.

This study was funded by the US National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Superfund Research Program, and the 2010 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

Full details of the study were published in the latest issue of the top scientific journal Nature Nanotechnology. The work represents the first time science provides an explanation for why cells become interested in the long nanotubes and fibers.

In the vast majority of cases, the team reports, long nanofibers enter the cell at an angle of about 90 degrees. Given that most nanoscale tubes have rounded tips, the cells confuse them for spheres, and act accordingly. However, as they try to engulf the long strands, they naturally fail.

After some time, cells figure out that they literally bit off more than they can chew, but this realization comes too late. “It’s as if we would eat a lollipop that’s longer than us. It would get stuck,” Brown professor of engineering Huajian Gao says. He is also the corresponding author of the new paper.

Once endocytosis – the process of engulfing a foreign object – begins, the cell cannot abort it even minutes later, once it realizes it has been deceived. “At this stage, it’s too late. It’s in trouble and calls for help, triggering an immune response that can cause repeated inflammation,” Gao explains.

The new results have tremendous implications for the field of nanotechnology, since nanoparticles are currently being groomed for use in a wide variety of medical applications. For instance, new therapies against cancer rely on drugs being delivered exclusively to tumors via spherical nanoparticles.

“If we can fully understand (nanomaterial-cell dynamics), we can make other tubes that can control how cells interact with nanomaterials and not be toxic. We ultimately want to stop the attraction between the nanotip and the cell,” Gao concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //