We already know, at least from the movies, that human witnesses are not always reliable. This new research made by a team at the UCL (University College London) and published in the journal "PLoS Computational Biology" has encountered a connection between what we expect to see and what our brain actually records, when reality is different. It appears that the context surrounding what we see, in many cases, results to shape more strongly what we believe we have seen than the proofs delivered by our eyes, making us imagine things that aren't really there or occurring.

A vague background lets our brain spur its imagination more than a bright, clear one. This explains why we perceive many fake images in the shadows.

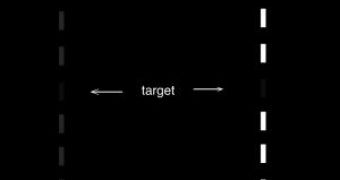

The researchers put 18 subjects to look at the center of a black computer screen. Each time they heard a buzz they pressed one of two buttons in order to register whether or not they had spotted a small, dim, gray rectangle in the center of the screen. In the case when the rectangle appeared, it was displayed for only 80 milliseconds.

"People saw the target much more often if it appeared in the middle of a vertical line of similar looking, gray rectangles, compared to when it appeared in the middle of a pattern of bright, white rectangles. They even registered 'seeing' the target when it wasn't actually there. This is because people are mentally better prepared to see something vague when the surrounding context is also vague. It made sense for them to see it -- so that's what happened. When the target didn't match the expectations set by the surrounding context, they saw it much less often," said lead author Professor Li Zhaoping.

"Illusionists have been alive to this phenomenon for years. When you see them throw a ball into the air, followed by a second ball, and then a third ball which 'magically' disappears, you wonder how they did it. In truth, there's often no third ball - it's just our brain being deceived by the context, telling us that we really did see three balls launched into the air, one after the other. Contrary to what one might expect, it is a vague rather than a bright and clearly visible context that most strongly permits our beliefs to override the evidence and fill in the blanks. In fact, a bright and clearly visible context actually overrides the evidence in the opposite direction - suppressing our 'seeing' of the vague target even when it is present. Mathematical modeling suggests that visual inference through context is processed in the brain beyond the primary visual cortex," added Zhaoping.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //