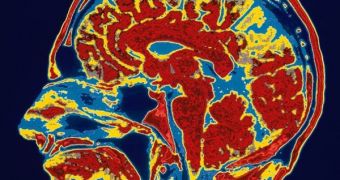

A new scientific paper, published in this week's edition of the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, comes to prove that the human brain doesn't have a single “God spot” in it, but rather that belief in a higher power is the trigger for increased activity in certain regions of the organ. For these conclusions, believers and atheists alike were questioned during an experiment, over the course of which their brains were hooked to functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) machines. The effect that various God-related statements produced on their minds were carefully recorded, and then analyzed and cross-referenced to their triggers.

According to the results of the brain scans, participants showed that they used more of their higher thought patterns when dealing with concepts associated with a higher being, such as the role of God in their lives, the attributes of the Creator, as well as when trying to decipher metaphors hidden behind religious teachings. For each attribute that was assigned to God, a different part of the brain “lit up” on the fMRI scans, further proving that there was no religious spot in the brain and that the entire cortex participated in the belief process.

“That suggests that religion is not a special case of a belief system, but evolved along with other belief and social cognitive abilities,” National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke cognitive neuroscientist Jordan Grafman, who works out of Bethesda, Maryland, told LiveScience.

For the first part of the study, the scientists set out to determine what people believed of God's involvement and intentions for the world, and sought to analyze personal experiences that each of the participants claimed to have had, rather than rely on religious doctrine alone. For the second part of the experiment, the participants were asked to respond to statements regarding the beliefs they expressed, and the reactions of their brains were recorded with the fMRI machine.

Thus, researchers learned that individuals tended to use their higher-function brain regions while attempting to sort their ideas of God and when handling concepts related to this idea. Parts of the brain linked to the theory of mind (ToM) failed to work properly when they tried to analyze the actions of a God involved with the world. On the other hand, it lit up significantly when participants sought to understand the actions of a detached higher being.

“Probably because we would tend to use theory of mind when we were puzzled, concerned, or threatened by another’s behavior. Reading a statement that you have been asked to compare your own personal beliefs with certainly will activate your own belief system,” Grafman explained. “The more interesting studies will wind up comparing different belief systems with similar dimensions to see if they also activate the same brain areas. If they do, we can better define why those brain areas evolved in humans,” he concluded.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //